- Home

- Our Stories

- 2013 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Tom Cheek

2013 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Tom Cheek

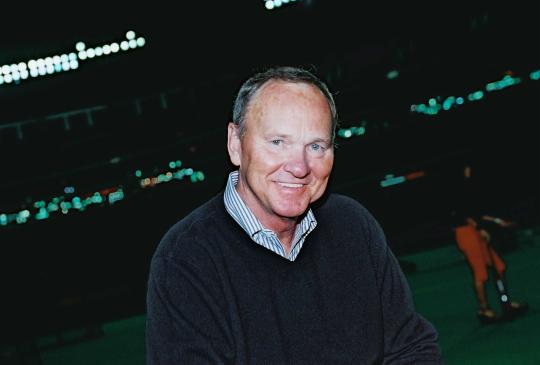

They are four digits that most Blue Jays fans – especially those who endured the growing pains of an expansion team – know by heart.

That’s because 4,306 represents not just the incredible number of consecutive regular-season Jays games Tom Cheek broadcast, but also the countless moments during those broadcasts where Cheek connected with his audience.

Cheek’s voice was silenced when he passed away on Oct. 9, 2005. But his legacy lives through the stories he brought to the fans – and is now celebrated in Cooperstown with the 2013 Ford C. Frick Award, which was posthumously awarded to Cheek.

“For Tom, if he were alive today, he'd say there are so many others who are more deserving of this award,” said Shirley Cheek, Tom’s widow. “He realized his dream when he joined the Blue Jays at age 37. When he got sick, he said he didn’t want to die so young, but that he did all the things he wanted to do.”

Born June 13, 1939 – one day after the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum opened its doors in Cooperstown – in Pensacola, Fla., Cheek was raised in a Navy family and joined the armed forces himself in 1957, serving in the Air Force until discharged in 1960. Cheek’s father, also named Tom, was a World War II hero who served as a fighter pilot in the Battle of Midway in 1942.

After continuing his education at SUNY Plattsburgh and the Cambridge School of Broadcasting in Boston, Cheek worked as a disc jockey in Plattsburgh, N.Y., and as sports director for a group of three stations in Burlington, Vt., calling University of Vermont sports for several years. In 1959, he married Shirley, a native of Hemmingford, Quebec. They had three children: Lisa, Jeffrey and Tom Jr.

In 1974, Cheek began work as a backup announcer to 2011 Frick Award winner Dave Van Horne on Expos broadcasts. Then in 1976 at the age of 37, he landed the job as the radio voice of the expansion Blue Jays. Paired first with Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn and later with Jerry Howarth starting in 1981, Cheek’s rich baritone voice and his passionate-yet-lighthearted approach to his job dazzled fans eager to embrace Toronto’s new role as an American League outpost.

After six losing seasons, the Blue Jays – under the leadership of Hall of Fame general manager Pat Gillick – evolved into one of baseball’s most consistent franchises in the mid-1980s. Cheek was right there in the middle of it – and remembered the game the Jays clinched their first division title in 1985 as one of his worst days in the booth.

“When George Bell dropped to his knees on the turf at Exhibition Stadium in 1985 as the Blue Jays won their first division title, I started thinking about all the guys who’d contributed over the year to get them there – and I choked up,” said Cheek in an interview the year before his death. “You could hear the catch in my throat. I promised I’d never do anything like that again.”

Over the next decade, Cheek had plenty of memorable moments in the booth – fighting off the emotions as the Jays won five American League East titles and two World Series crowns from 1985-93.

His call of Joe Carter’s World Series-winning home run in Game 6 of the 1993 Fall Classic – “Touch ’em all Joe! You’ll never hit a bigger home run in your life.” – quickly became embedded in the sports conscious of Blue Jays fans around the globe.

Cheek called every regular season and postseason Blue Jays game from the franchise’s birth on April 7, 1977 through June 2, 2004. But by the end of June, his life had taken a dramatic turn.

“It takes a lot to keep a streak like that alive,” said Howarth, Cheek’s longtime broadcast partner. “It’s a testament to his professionalism, to his commitment to fans.”

On June 3, Cheek took the first of two days off to attend the funeral of his father. Upon his return, Cheek sensed he was not right physically when he was unable to retain information he had read only minutes earlier. On June 13, 2004 – his 65th birthday – Cheek underwent surgery to remove a brain tumor, but some of the tumor was unreachable.

“There were no headaches, none of that stuff,” said Cheek, who maintained his presence in the broadcast booth as much as possible, skipping road trips while still calling games at SkyDome. “It all happened in three days.”

A little more than a year after the surgery, Cheek passed away.

Before his death, Cheek considered what he might like engraved on his tombstone in an interview with the Toronto Star’s Chris Zelkovich. In typical Cheek fashion, he downplayed his exceptional talent.

“He loved the ride,” Cheek said of his epitaph. “And he tried to do his best.”

Cheek was inducted into the Blue Jays Level of Excellence in 2005. That same year, the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame established the Tom Cheek Media Leadership Award, with Cheek being honored with the first award.

“I’ve never had any delusions about being in Cooperstown,” Cheek said when he first appeared on the Frick Award ballot. “I don’t allow myself to think in those terms.”

For others, however, Cheek’s status as a Hall of Fame-caliber broadcaster was never in doubt.

“The game of baseball provided us the most amazing years,” said Shirley Cheek. “We were treated so well by the Blue Jays.”

More Frick Award Winners

Hall of Fame Awards

Related Stories

Nolan Ryan tosses his fourth no-hitter

League of Women Ballplayers

A Scout’s Path to Cooperstown

Bobby Doerr reflects on a life in baseball

Fresh off AL pennant, White Sox bring back legendary Miñoso

Astrodome barely contains Mike Schmidt’s blast

1969 Hall of Fame Game

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr01c

01.01.2023

Ten Named To Golden Era Ballot for Baseball Hall of Fame Election

01.01.2023

BA MSS 67, Folder 15, Corr_1946_4_9a

01.01.2023

Treasures from 2014 World Series Headed Home to Cooperstown

01.01.2023