- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Montefusco

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Montefusco

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

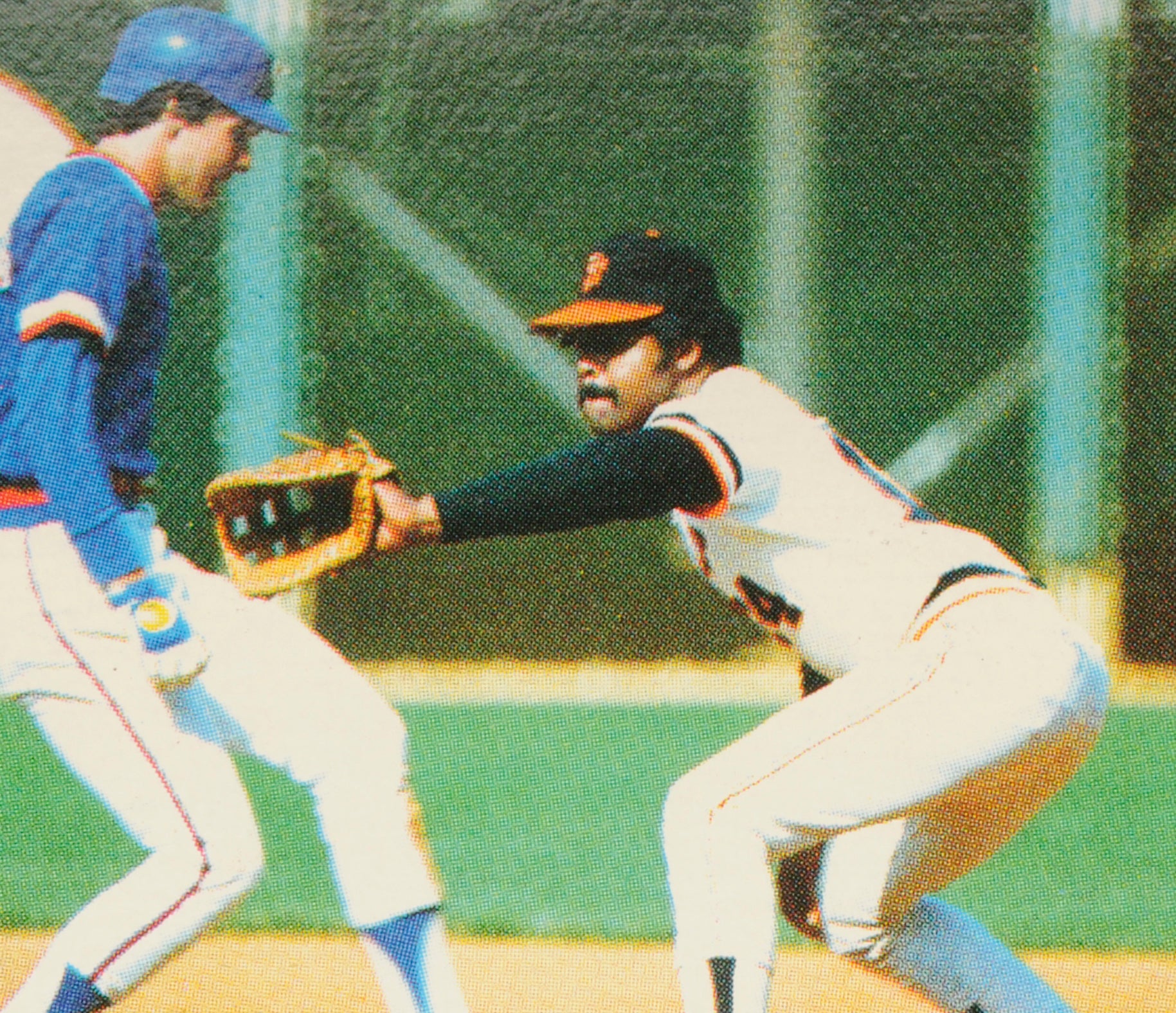

It seems only fitting that a card depicting John Montefusco comes with some intrigue. “The Count,” as he came to be known, was one of the most colorful and controversial players of his era. To be sure, his 1983 Topps card gives us some fodder for speculation.

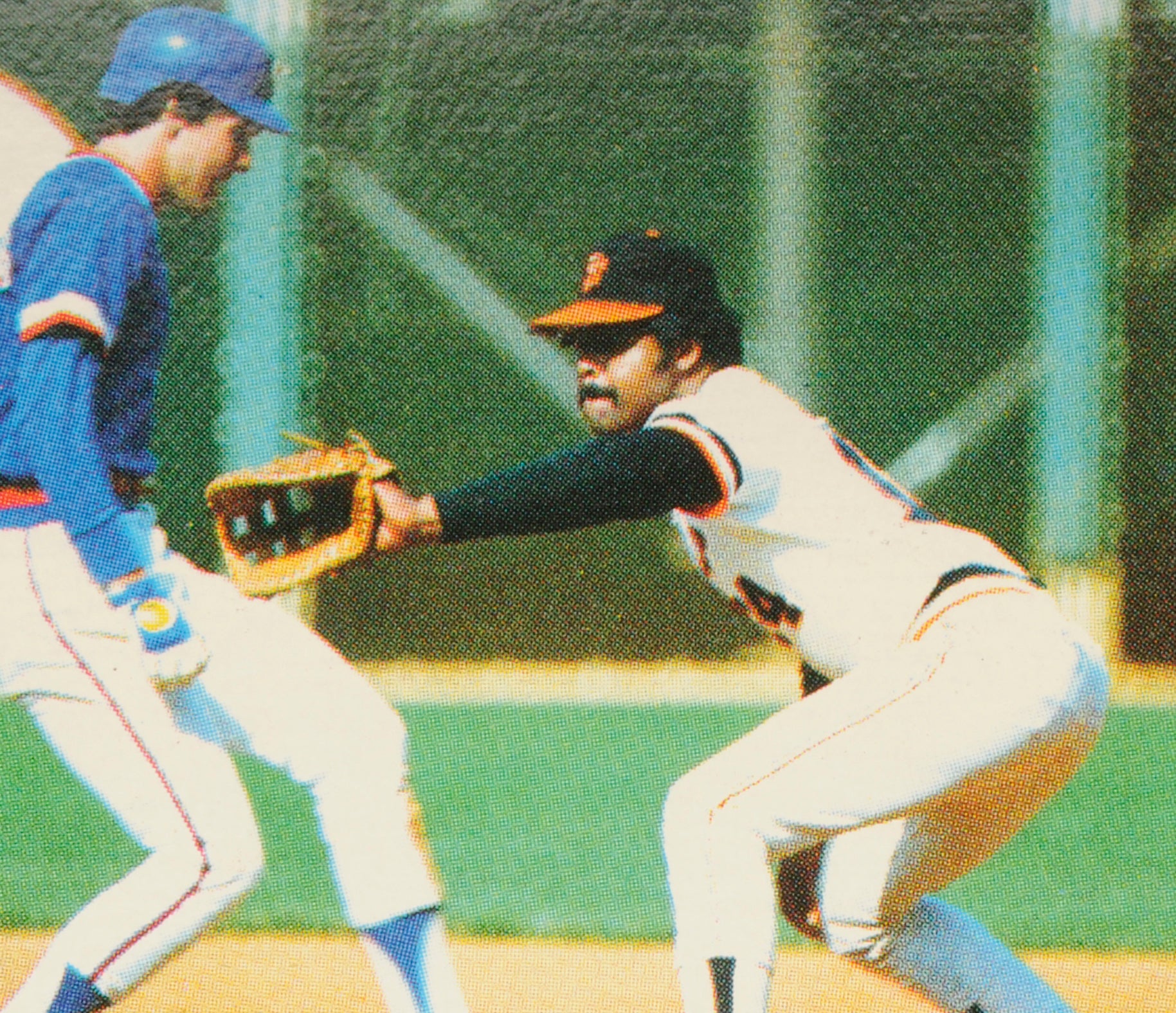

The larger photograph on Montefusco’s card gives us a good look at the tall right-hander standing on the mound, presumably during Spring Training in 1982. At the time, the Padres trained in Yuma, Ariz. It’s a good shot of Montefusco, eyeing the catcher for a sign while holding his hands together, but nothing out of the ordinary. No, the intrigue comes with the background of the photograph. What exactly is that behind The Count?

At first glance, it looks like a wire mesh fence in front of an apartment building. But upon a second review, I may be wrong. At least one blogger I’ve read claims that to be a parking lot located behind the fence. And what exactly is that strange fence made of? It looks a little like mosquito netting. Or maybe camouflage covering used in an Army base? Given the blurriness off the background, it’s hard to say with any certainty. But it looks weird, less like the standard fence found on a practice ballfield in Spring Training and more like camouflage used at a military compound during wartime.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

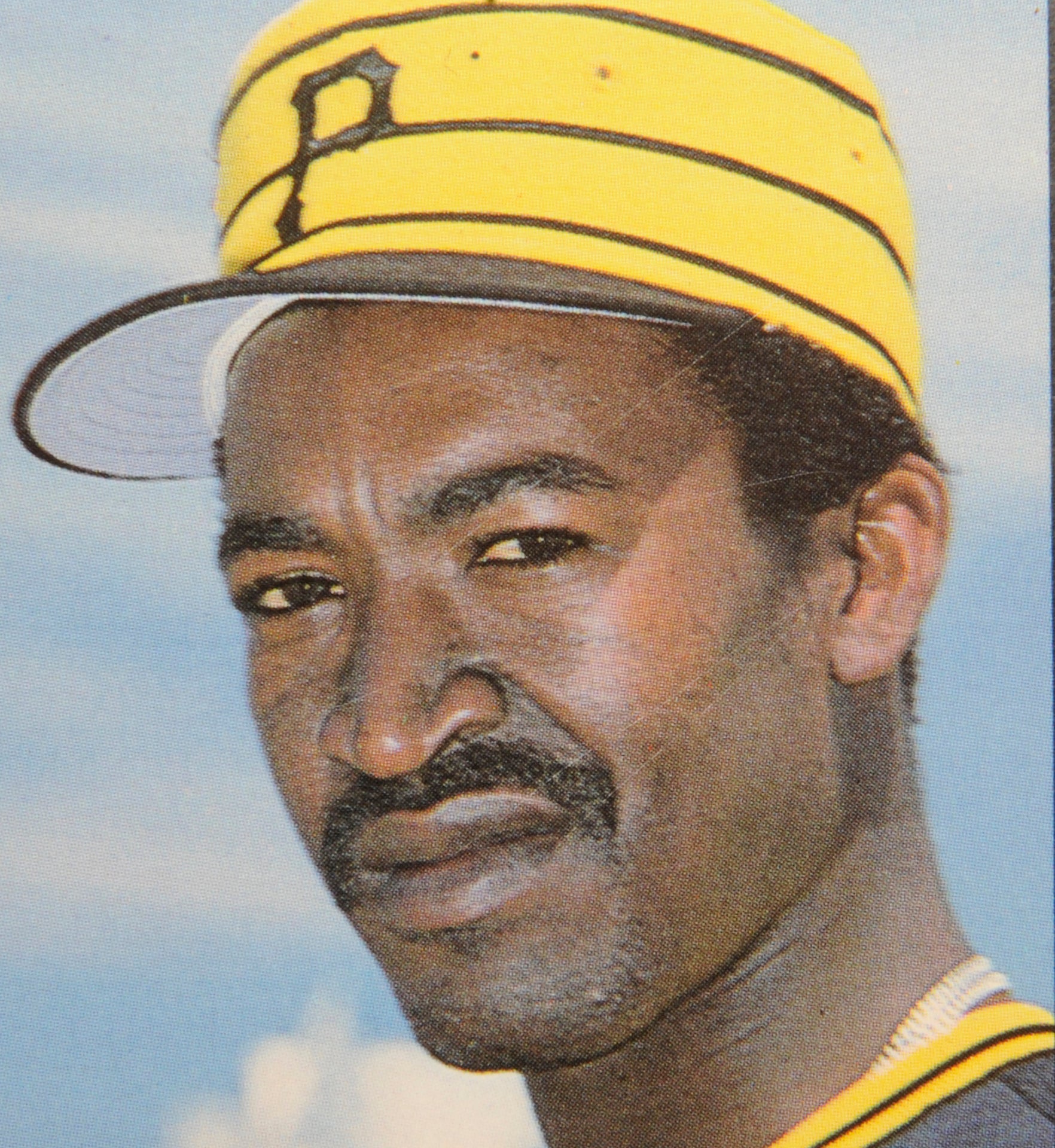

Then there is the inset photo of Montefusco, which shows him flashing that trademark mischievous grin of his. On a few of his cards, such as his 1981 Topps, 1982 Fleer, 1983 and ’84 Donruss cards, we see Montefusco with a similar smile. After all, Montefusco loved to make outlandish statements. Here he looks like a guy who knows he’s about to say something outrageous, something that will get other people’s blood boiling.

Right from the start of his professional career, John Montefusco established a reputation for brash words and flamboyant behavior. Shortly after reporting the Giants’ affiliate in the Midwest League, he predicted that he would make the big leagues within two years. He backed up the bravado early on, striking out 126 batters in 120 innings during his debut minor league season in 1973. Duly impressed, the Giants moved him up to Double-A Amarillo in 1974, followed by a midseason promotion to Triple-A Phoenix. The fast-rising Montefusco completed the climb in September, making his debut for San Francisco on Sept. 4 and fulfilling his prediction of a call-up within two years. In seven late-season appearances for the Giants, he showed off his live fastball, but also struggled with his control.

Montefusco also earned his new nickname from Giants broadcaster Al Michaels, who dubbed him “The Count of Montefusco,” a pun based on his last name’s similarity to “Monte Cristo.” (As a minor leaguer, Montefusco was once called “The Count of Monty Amarillo,” but that moniker did not catch on in the same way as the Michaels nickname.)

Given Montefusco’s talent and their own need for starting pitching, the Giants made him a fulltime member of their starting rotation in 1975. The young right-hander did not disappoint. He made 34 starts, won 15 of them, and struck out 215 batters in 243 innings. Emerging as something of a mini-sensation, Montefusco earned Rookie of the Year honors and also finished fourth in the National League’s Cy Young balloting. Some Giants fan began to refer to Montefusco as the successor to the great Juan Marichal.

Unlike Marichal, Montefusco spoke often and loudly. His proclivity for bold predictions earned him another nickname: “The Mouth that Roared.” As he prepared to face the Cincinnati Reds during his rookie season, Montefusco boldly told the press that he would pitch a shutout – and strike out Johnny Bench four times! Those predictions of grandeur failed on both counts. The Count allowed seven runs in a third of an inning, while surrendering a three-run blast to Bench.

Montefusco’s flop against the Reds was his one major blip as a rookie. Other than that, he pitched at the level of an ace. His success only seemed to make him brasher upon arriving at Spring Training in 1976. When he heard Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley suggest that the A’s and Giants play an exhibition game, Montefusco expressed his support, largely because it would give him the chance to face Reggie Jackson.

“I know I would strike out Jackson four times. Easy,” Montefusco matter-of-factly told Glenn Schwartz of the San Francisco Examiner. That same spring, Montefusco criticized the head of the Players’ Association, Marvin Miller, and fellow pitcher Andy Messersmith for challenging the game’s reserve clause. He blamed both for causing the delay to the start of Spring Training, which had been necessitated by ongoing negotiations between players and owners.

On the field, Montefusco showed few signs of faltering, as he lowered his ERA to 2.84, won 16 games, and led the league with six shutouts. Montefusco capped off his performance by pitching his best game on the final day of the season. Facing the Atlanta Braves, Montefusco fired a no-hitter, a fitting end to a second summer of dominance.

When a reporter asked Montefusco if the no-hitter might lead him to become quieter, to simply allow his actions to speak for themselves, he offered up a response that epitomized his Count persona. “You kidding?” Montefusco said in an interview with the Atlanta Constitution. “I’ll be talking about this all winter. They’ll never shut me up now.”

Montefusco enjoyed the winter, but could not sustain his established level of success into 1977. On May 26, he sprained his ankle while running toward first base. The sprain forced him to the disabled list, where he remained for more than five weeks. And then after his return, Montefusco injured his elbow late in the season.

The injury would have long-lasting effect, resulting in him changing his approach, from that of a power pitcher to a sinkerballer. In response to the injury, Montefusco adopted an unusual motion. He now appeared to hunch his back while delivering the ball from a three-quarters arm slot.

Not only did 1977 bring arm woes, but it also brought on controversy. Montefusco feuded with members of the San Francisco media. Among others, he refused to be interviewed by beloved Giants broadcaster Lon Simmons. His freeze-out of Simmons only led to more criticism coming from Giants beat writers and Bay Area columnists like Wells Twombly and Glenn Dickey.

In 1978, Montefusco found himself in the middle of more controversy, again because of his penchant for speaking too honestly and without a filter. During the early days of Spring Training, he publicly criticized the fielding of Giants second baseman Bill Madlock, who was more suited to playing third base. Madlock did not appreciate the criticism. On March 8, he approached Montefusco. The two became entangled in a fight.

Montefusco escaped injury on that occasion, but not on another. In early April, Montefusco stepped off the mound, landed oddly on his foot, and sprained his ankle. In spite of the injury, Montefusco made 36 starts and logged 238 innings. For the season, he posted a career-worst ERA of 3.81, but still won 11 games.

That would turn out to be Montefusco’s last winning season in San Francisco. Limited to only 22 starts in 1979, he won a total of three games. It was a season filled with dissension for the Giants. Two Giants players, Roger Metzger and Ed Whitson, brawled with each other. And then, after losing a game to the Chicago Cubs, Montefusco abruptly left Candlestick Park, vowing to never again return. He did, but he clearly remained unhappy in San Francisco.

The situation reached a boiling point in 1980. On June 19, manager Dave Bristol pulled Montefusco from a game in the ninth inning, despite the Giants having a big lead. Montefusco wanted the opportunity to finish the game. Although the Giants’ bullpen held on for the win, Montefusco and Bristol exchanged angry words in the manager’s office. When other Giants players returned to the clubhouse, they found the two combatants wrestling on the floor of the manager’s office. It was an incident that The Count would come to regret.

The brawl with his manager, coupled with a 4.37 ERA, convinced the Giants that it was time to move on. After the season, the Giants traded Montefusco, sending him to Atlanta as part of a package for veteran right-hander Doyle Alexander.

Montefusco pitched most of the 1981 season out of the bullpen, where he compiled mediocre numbers while having to deal with the hitter-friendly conditions of Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium. The strike also wiped out part of the season, making it more difficult for Montefusco to gain traction in Atlanta. Once again, The Count could not escape controversy. He missed the team’s final series of the season, scheduled for Cincinnati. Montefusco claimed that his manager, Bobby Cox, had given him permission to skip the series. The Braves felt otherwise and announced that Montefusco would sit out the balance of the season on suspension.

Upset about the way the season ended, Montefusco asked the Braves for a trade. Later on, he amended the request, perhaps aware that he was about to become a free agent. With his performance clearly in decline, he found little interest at first, and did not sign a contract until well after Spring Training began. In March, he finally signed a bargain basement deal with the pitching-needy San Diego Padres.

After a lackluster 1982, Montefusco found one last return to glory in 1983, the same year of his Topps card. He pitched so well for the non-contending Padres that he drew late-season trade interest from the New York Yankees, who gave up two players to be named later in an August trade. Almost single-handedly, Montefusco helped the Yankees stay in the American League East race, as he went 5-0 with a 3.32 ERA. But the other Yankees pitchers didn’t carry their share of the load, resulting in a third-place finish.

Montefusco’s Herculean effort down the stretch convinced the Yankees to re-sign him as a free agent. They hoped he could repeat some of that late-season magic in 1984, but one injury after another derailed him. At first, he came up with a sore hip. In May, he became involved in a car accident that forced him onto the disabled list. And then he came down with a blister on his pitching hand. On the few occasions that Montefusco pitched, he pitched well, but he made only 11 starts and won just six games.

The situation only worsened in 1985. Developing a sciatic condition in his hip, he missed almost the entire season. Frustrated by his inability to pitch for a Yankees team that lost the division by only two games, Montefusco felt responsible for the team falling short. “I felt like I was the cause of us not going to the playoffs, because we only missed by a game or two,” Montefusco told YES Network. “I think if I would’ve been here the whole year, we could’ve made it.”

That winter, Montefusco underwent a procedure in which surgeons drilled two holes into his hip. The Yankees released him, but Montefusco was determined to make a comeback. He rehabbed the injury and convinced the team to give him another look in 1986. The Yankees resigned him on May 15 and inserted him into the bullpen, where he delivered four consecutive scoreless appearances. But the pain in his hip returned, doctors determining that he was suffering from a degenerative condition. Montefusco wanted to keep pitching, but by September he realized that his desires were futile. He announced his retirement, ending his major league career 11 years after it started.

In order to deal with the pain of his hip condition, Montefusco was prescribed with a drug called Percocet. He soon became addicted. That led to the abuse of several other prescription drugs, including Xanax, an antidepressant.

Montefusco eventually entered rehabilitation and kicked his addiction, but another problem soon developed. In the mid-1990s, Montefusco’s wife filed charges that he had committed aggravated sexual assault and made terrorist threats against her. Unable to afford the $1 million in bail money, he spent two years in jail awaiting trial. Those two years pushed Montefusco to the brink. On two occasions, he was beaten up, once by an accused murderer. “There were times when they gave out razors to shave,” Montefusco told the Oakland Tribune, “they gave them out once a week. I wanted to take the blade out and just end it, because it was hard there.”

Thankfully, Montefusco resisted that option. All along, he maintained his innocence, claiming that his wife had twisted the circumstances of their marital difficulties. Subsequent newspaper accounts, including a passionate defense from New York Post sportswriter Phil Mushnick, indicated that many of his wife’s charges may have been exaggerated, if not completely made up.

Receiving his day in court, Montefusco was eventually acquitted of all felony charges, 14 counts in total. It took a jury only three hours to render the verdict. As part of the jury’s finding, Montefusco was given only probation on lesser charges of criminal trespass and simple assault.

That was the good news. The bad news? Montefusco was virtually penniless. He also had no home, no car and no job.

Determined to rebuild his life, The Count gained a level of reacceptance when the Giants invited him to Pac Bell Park to participate in a reunion of the Giants’ 1978 team. More importantly, found work in independent minor league baseball. He became Sparky Lyle’s pitching coach with the Atlantic League’s Somerset Patriots. Under Montefusco’s direction, the Patriots’ standout pitching staffs led the team to two league titles. Montefusco remained with the Patriots through 2005, when he resigned as a coach and expressed a desire to manage, but that opportunity never came.

A few years back, I had the chance to meet Montefusco as he visited Cooperstown to sign autographs at the local CVS Pharmacy. Montefusco took only a small payment, with most of the proceeds going to a cancer-stricken employee of the company.

Montefusco stayed after his allotted time to make sure all autograph seekers were accommodated. Montefusco was somewhat reserved, almost shy, nothing like the brash Count who had become the stuff of legend. He talked to the fans quietly, and as he did, I heard him mention his hopes for the future. He said he wanted to return to baseball with the Giants as a minor league pitching instructor. According to some of the people who knew him from his days coaching in independent minor league ball, Montefusco was particularly good at breaking down a pitcher’s mechanics, a valuable skill for any pitching coach.

For whatever reason, Montefusco never did return to the Giants’ organization, but did receive satisfaction in another area, when the Yankees finally invited him to Old-Timers Day in 2014. It was the same day that his former teammate, Goose Gossage, received a monument at Yankee Stadium.

“I couldn’t be any prouder, really,” The Count told the YES Network. “And to be with the guys that are here today, and for Goose to have the day that he’s going to have today, it’s nice to be here.”

On that day, there were no bold predictions, no more controversies. Even if only for a day, a humbler and happier John Montefusco found himself back in the big leagues.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps and 1983 Fleer Dave Collins

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps and 1983 Fleer Dave Collins