- Home

- Our Stories

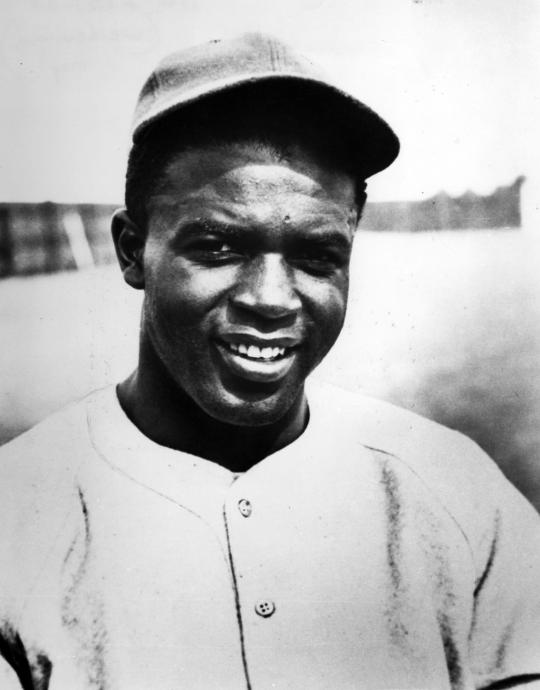

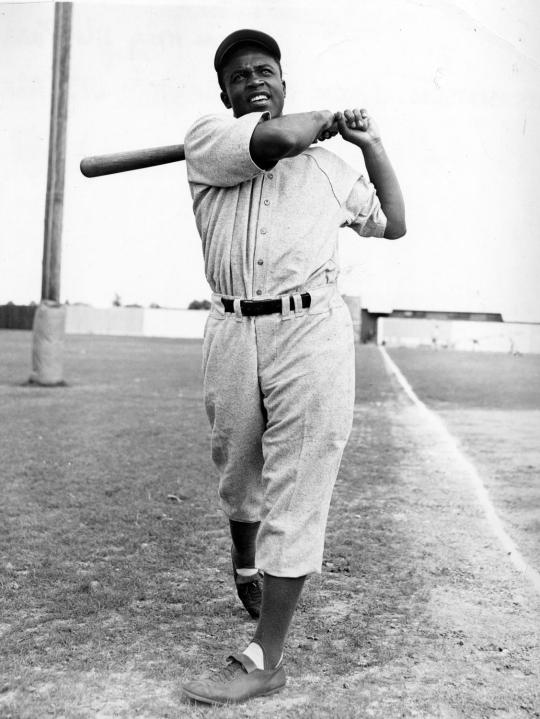

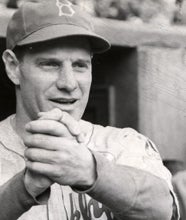

- Jackie Robinson, circa 1946

Jackie Robinson, circa 1946

Sometimes life is all about being in the right place at the right time.

For one young boy in 1946, being in the right place at the right time made him a participant in history.

As the Brooklyn Dodgers descended upon Daytona Beach for spring training that year, the team had a new player – one who would break barriers that had stood in baseball 60 years.

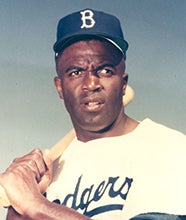

Following the 1945 season, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey made the well-documented signing of Jackie Robinson. Fresh off a season with the Negro American League’s Kansas City Monarchs, Robinson would be the first African American to play in the major leagues – or in so-called “organized baseball,” for that matter – since the late 1800s.

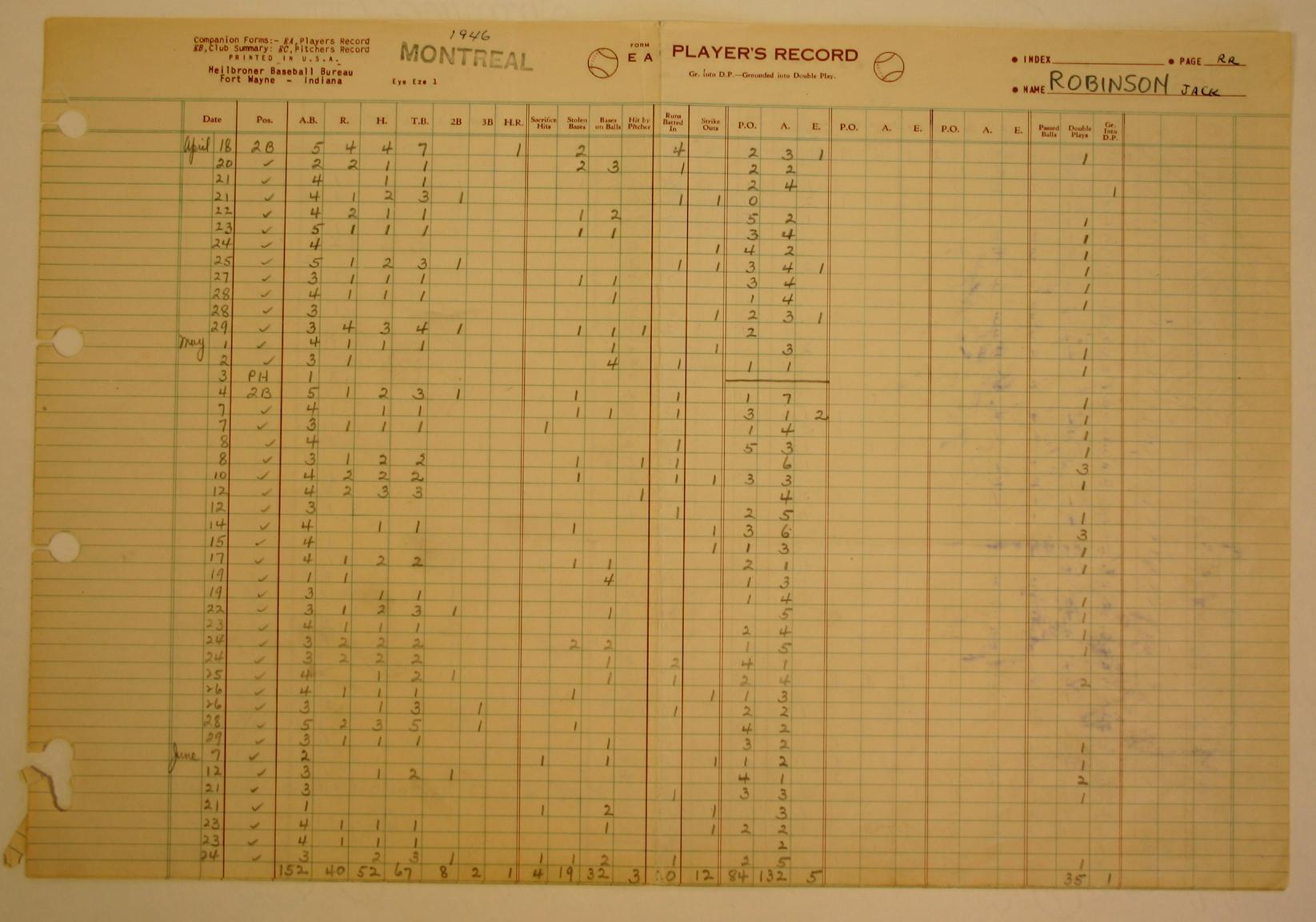

Rickey’s plan was to give Robinson a year of seasoning with their Triple-A farm club, the Montreal Royals, before elevating him to the big club. This way, Robinson would get the professional experience he needed to determine his readiness for the major leagues.

A trip to Florida

As Robinson and his wife, Rachel, traveled to Daytona Beach in the winter of 1946, so too did young George Bates. Bates, about 10 years old at the time, came to Florida with his father and brother, both named Robert. The Bates family, from Norwalk, Conn., came to the Sunshine State because the weather was more preferable for the elder Robert Bates’ occupation: Painting.

“This was our winter deal,” George Bates recalled in a recent interview. “My father came to paint houses over the winter. We lived in Port Orange.”

“We only did this two or three times.”

Port Orange, located a short drive south of Daytona Beach, was a sleepy town in the 1940s. According to the 1940 United States Census, the population was just shy of 700 people. Daytona Beach only had around 22,500 residents.

While Daytona Beach would bear witness to the integration of professional baseball in 1946, Port Orange was no stranger to African Americans seeking fresh opportunities. Following the Civil War, Dr. John Milton Hawks, an abolitionist and surgeon in the Union Army, brought 500 freed slaves to a settlement that was named Port Orange. Though some families left during tough times, the African American roots remain in an area informally known as Freemanville. Mount Moriah Baptist Church is also a lasting reminder of the town’s early settlement.

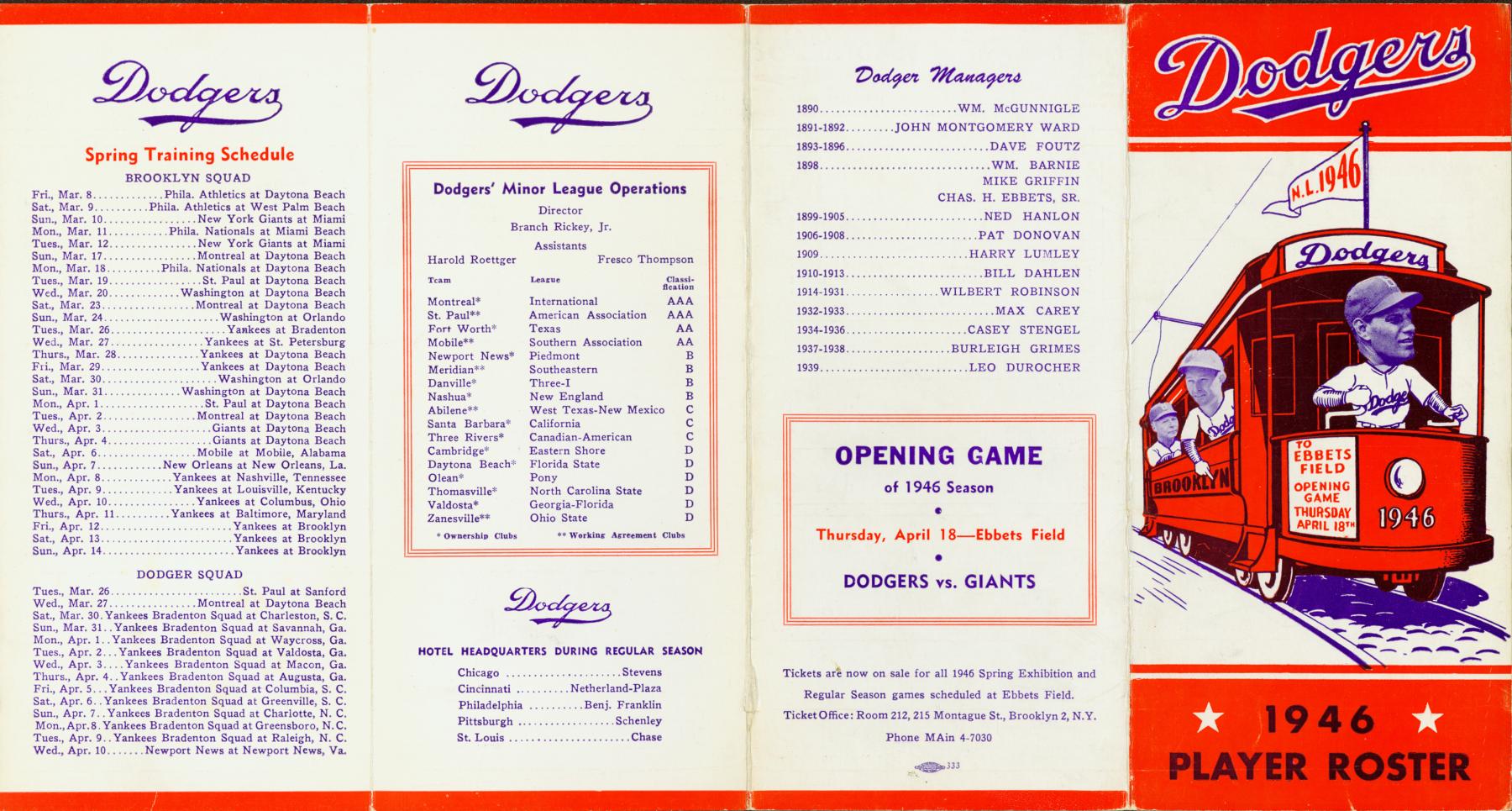

Heading to Daytona Beach in 1946 also meant a chance to see the Bates family’s beloved Brooklyn Dodgers, who were once again spending spring training in Florida after three wartime spring trainings at Bear Mountain, N.Y.

George Bates grew up a Dodgers fans and noted that they “would sometimes take the train or a car to Brooklyn to go to games at Ebbets Field.”

“I wanted to see the Dodgers in person and to see the (Sym-phony) band,” he said.

On the field

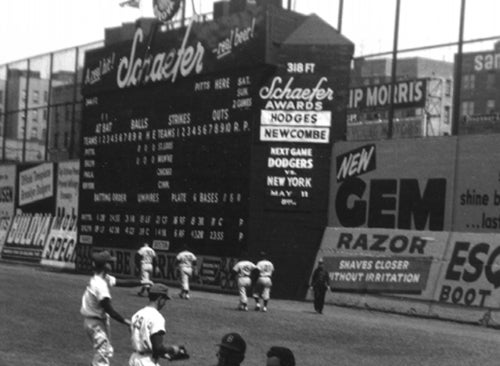

In 1946, the Dodgers played their spring training home games at City Island Park in Daytona Beach, while one of their top farm clubs, the Montreal Royals, worked out at Kelly Field. (The Dodgers’ other top farm club, the St. Paul Saints, held spring training in Sanford, around 40 miles southwest of Daytona Beach.) On St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, Jackie Robinson and the Royals came to City Island Park to face the Dodgers in the first spring meeting of the two clubs. It would also be the first game Robinson played as a member of the Brooklyn organization, though Rickey would not attend, owing to the fact that the game was on a Sunday. Attending the match, however, were over 4,000 fans, which included almost 1,000 African Americans. As the New York Times’ Roscoe McGowen reported:

“There was an overflow crowd of Negro spectators – nearly 1,000 – and the small Jim Crow bleacher section allotted to them was entirely inadequate, many of them standing out beyond the right-field foul line.”

Robinson played the first five innings at second base and batted sixth in the order. He cleanly handled two chances in the field. Though he went 0-for-3 at the plate, Robinson did reach on a force play, stole second base, and scored on catcher Ferrell Anderson’s base hit. The Dodgers won 7-2.

“I’ve sure been looking at some beautiful curves,” Robinson told the Brooklyn Eagle. “I just couldn’t hit ’em all.”

The crowd’s reaction to Robinson’s debut was mixed. The Associated Press reported that the African-American fans applauded Robinson when he came up for the first time, but the white fans did not applaud until Billy Herman caught Robinson’s foul fly. Both groups applauded Robinson in his other two at bats, though on those occasions, the Brooklyn Eagle claimed “Robinson was booed mildly.”

The next day, Montreal and St. Paul faced off at Kelly Field, with the Royals taking a 1-0 decision. Robinson had three hits and African-American pitcher John Wright pitched five innings for Montreal, allowing one run on five hits.

Under the microscope for his first game, Robinson later said he was “thinking so many other things he didn’t know just what he was doing.”

Preserved on film

The Dodgers would play the Montreal Royals twice more in preseason exhibitions, with the last game on April 2 at City Island Ballpark.

Part of what happened that day has been recorded on film and will remain forever in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library, as well as in the memory of George Bates.

In Florida, Robert S. Bates, George’s father, filmed some of their trip, which included parts of the April 2 game between Brooklyn and Montreal, along with a bit of the next day’s game between the Dodgers and Giants. George later donated that footage to the Hall of Fame.

The footage is significant in that it is perhaps the earliest known recording – in color, no less – of Jackie Robinson playing for Montreal. But the day held more significance for young George and his brother, Robert L. Bates. The two boys were the batboys for that game.

As it turns out, it was a completely random moment.

“They spotted us and told us we needed bat boys,” George Bates recalled. “(Dodgers manager) Leo Durocher canned us after the second day when they got their bat boys. I don’t know why they didn’t have them there the whole time.”

George Bates served as Montreal’s bat boy that day – in the film, he is the boy with the dark pants and plaid shirt. His brother, in dark pants and a white shirt, handled the chores for the Dodgers.

“It was our decision to choose which teams (we were bat boy for), and we switched the next day,” Bates said.

Being a bat boy has its perks – you can meet all your baseball heroes – but it also has its unique aspects.

“The whole team was there. Gil Hodges, [Pee Wee] Reese,” Bates remembered. “I met Pee Wee Reese. I went to the drug store across the street to get him chewing tobacco. I guess that wouldn’t happen today.”

But being the bat boy for the Montreal Royals also meant getting a chance to interact with Robinson, though in Bates’ case, it was rather limited interaction.

“I just said something to him when he came up to bat – ‘Show ’em Jackie!’” Bates said. “But he walked by me without saying much.”

That day, Robinson let his play do the talking.

Against a Dodger team missing many of its key components, and under the full view of Branch Rickey, the Royals built a six-run lead and defeated Brooklyn 6-1 at City Island Park on April 2.

Robinson, once again playing second base and batting sixth, played the entire day and got two hits off Dodgers starting pitcher Ed Chandler. One of those hits, probably the second, was captured on film. At the 1:55 mark, we see an African American wearing number 9 heading to the on-deck circle, passing George Bates, as Royals shortstop Louis Welaj comes to the plate.

Though much of the focus is on George Bates the bat boy – the elder Bates filmed the action, and he does make a brief cameo toward the end – there is some game action. As the runner breaks from first, we see Robinson hit Chandler’s pitch, possibly into left field. Over-running first base – and nearly halfway to second – Robinson returns to first safely, just beating the tag.

With Robinson safe at first with a base hit, the footage returns, for the most part, to the Bates brothers, with their father moving from one side of the ballpark to the other in order to capture the moments.

In the game, Robinson went 2-for-3 with a run scored and a stolen base. He had four assists in the field and took part in a double play.

Reaction to history

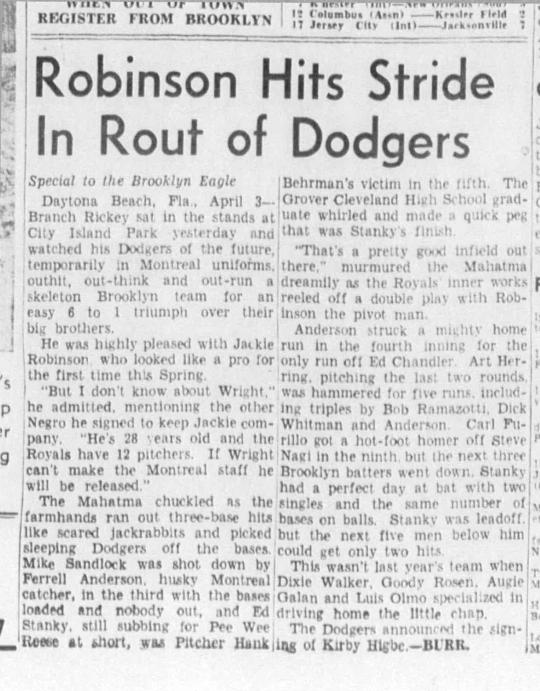

Rickey was very pleased with what he saw on April 2, the Brooklyn Eagle reported:

“The Mahatma chuckled as the farmhands ran out three-base hits like scared jackrabbits and picked sleeping Dodgers off the bases. … ‘That’s a pretty good infield out there,’ murmured the Mahatma dreamily as the Royals’ inner works reeled off a double play with Robinson as the pivot man.”

Eagle columnist Tommy Holmes described how the wooden stands beyond right field, where the African-American fans sat, “literally shook with a spasm of hysteria” when Robinson connected for his first hit.

Not all fans shared in that reaction, however. Holmes explained that when Robinson fouled out in his next plate appearance, a “young woman in the white stands screamed ‘Goody. Goody.’”

“I suppose that indicates an anti-Robinson faction present,” Holmes wondered. “Down here, would that surprise anybody?”

Yet, above all, Rickey seemed pleased with Robinson’s prospects.

Rickey noted to Holmes that at Kelly Field, where the Royals practiced, “(Robinson) has been hitting hard, but he seems to be pressing in exhibitions” at City Island Park.

The Mahatma then went on to predict that Robinson would “make the Montreal team this year, and he definitely is a big league prospect.”

Robinson, for his part, told Holmes that he felt “a real sense of responsibility” and that he had been treated well by his teammates, whose attitude he was pleased with and “who have been fine about everything.”

“In my early days down here, I was conscious, or thought I was, of a feeling of resentment among a few players but that has worn off,” Robinson said. “Only the other day one of the men who I thought resented us (meaning Robinson and John Wright, the other Negro in the Montreal camp) was over on the side of the field showing John some tricks of the pitching trade. “If I can’t play with Montreal, I’ll try to play wherever they want to send me. I feel that I owe that much to Mr. Rickey for this opportunity.” George Bates can also thank the Dodgers for his opportunity to be a part of history. The film ends with some footage of the New York Giants during their game against the Dodgers at City Island Park on April 3. The elder Robert Bates is seen drinking water out of a cup. Among the souvenirs George Bates took from his batboy experience was a baseball bat he received from the Giants, although he says the signatures are difficult to read. But the better souvenirs are the memories from being associated with such an historic moment. More than 40 years after Jackie Robinson’s debut in Daytona Beach, the ballpark, which today remains in use for minor league baseball, was renamed for the Dodgers star. After the 1989 renaming, Bates had an opportunity to return to the vastly improved ballpark and throw a ceremonial first pitch before a game. In the mid-1990s, Bates graciously donated his film footage to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Baseball fans across the country will be able to view some of this footage in Florentine Films’ upcoming documentary on Robinson. While those fans will be able to relive Robinson’s on-field feats, George Bates can see the film and know that he saw history unfold right before his very own young eyes.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum thanks George Bates for his donation and for his permission in allowing us to use the footage for this story.