- Home

- Our Stories

- Un-permanent records fill baseball history

Un-permanent records fill baseball history

Big league baseball has been enamored with numbers for most of the past 150 years, but some of its most celebrated achievements can’t always be chiseled in history.

The biggest names in the sport are often lauded because of their impressive statistics, but on those rare occasions, under a “woulda – coulda – shoulda” banner, certain records, milestones and accomplishments are proven to be either incorrect, altered or misidentified.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

The National Pastime’s past is not as set-in-stone as one might expect, with specific details of its story often muddled. With its record-keeping, especially in its nascent decades, not as meticulous it has been in recent years, it often comes down to the work of historians and researchers to uncover the details that change long-held beliefs.

In a sport where numbers matter, understanding the vagaries in its recorded history is important.

An early example of this, involving greats Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby, is referenced in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s exhibit, One for the Books, which celebrates baseball records and the stories behind them.

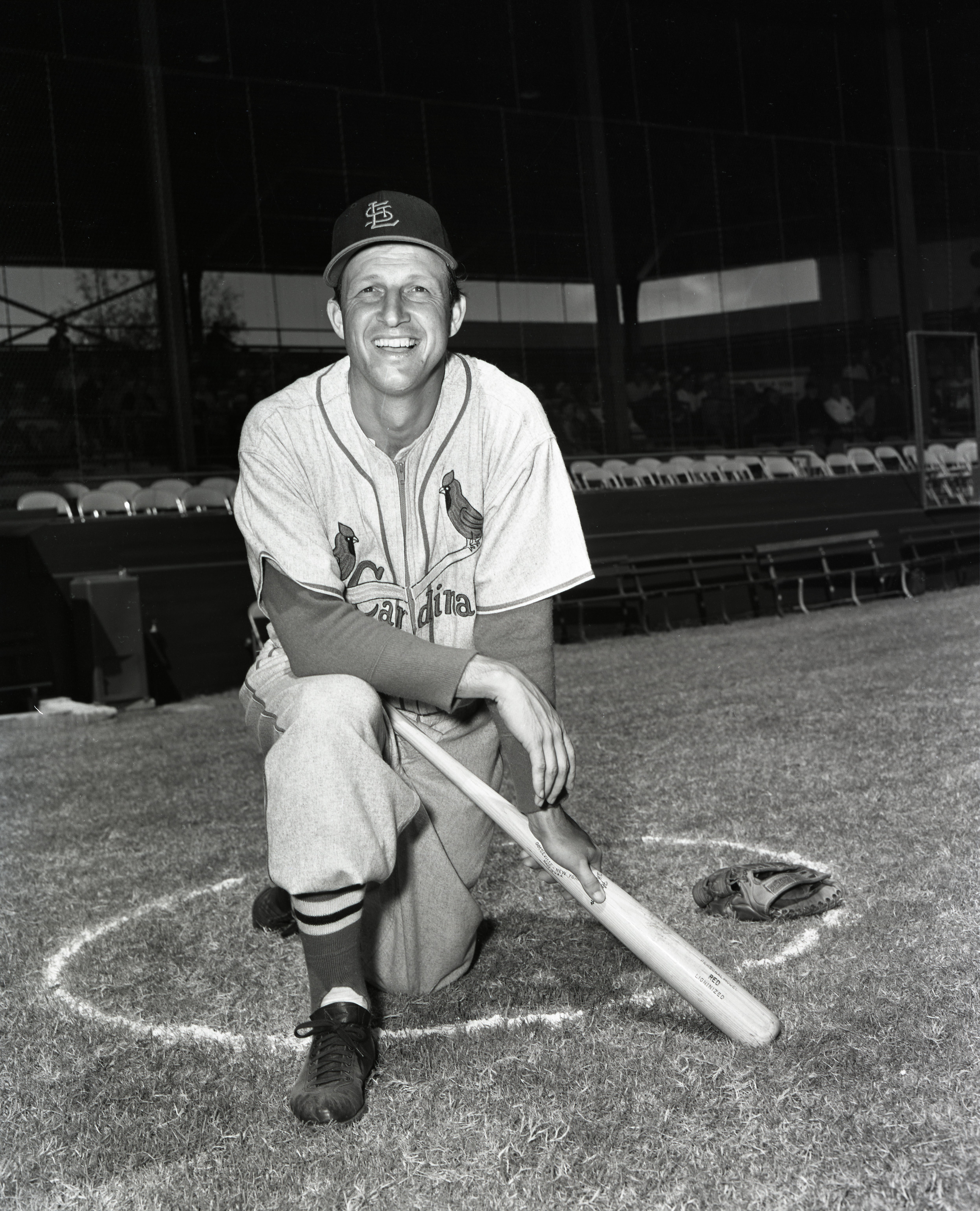

For years it was thought that Cobb held the record for most consecutive years leading the league in batting average, with the Tigers star topping the Junior Circuit for nine straight seasons from 1907 to 1915. But research done in the 1970s showed a discrepancy in the 1910 statistics that proved that Cleveland’s Nap Lajoie, in fact, should have been accorded the honor of a batting title, as he topped Cobb, .384 to .383.

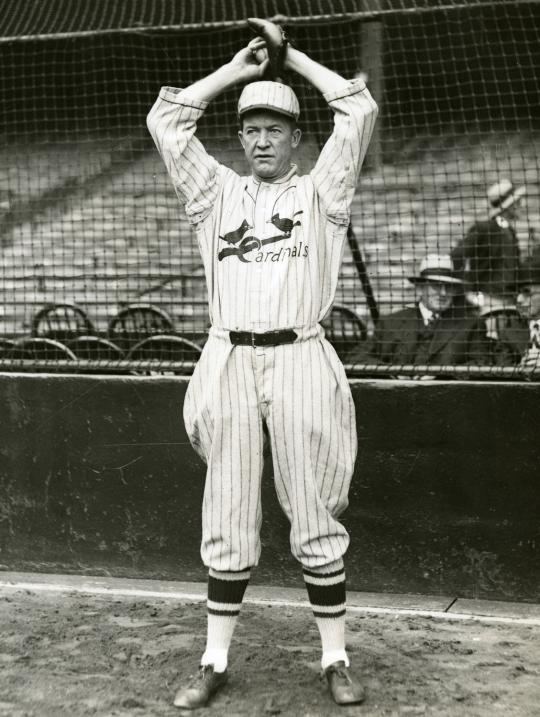

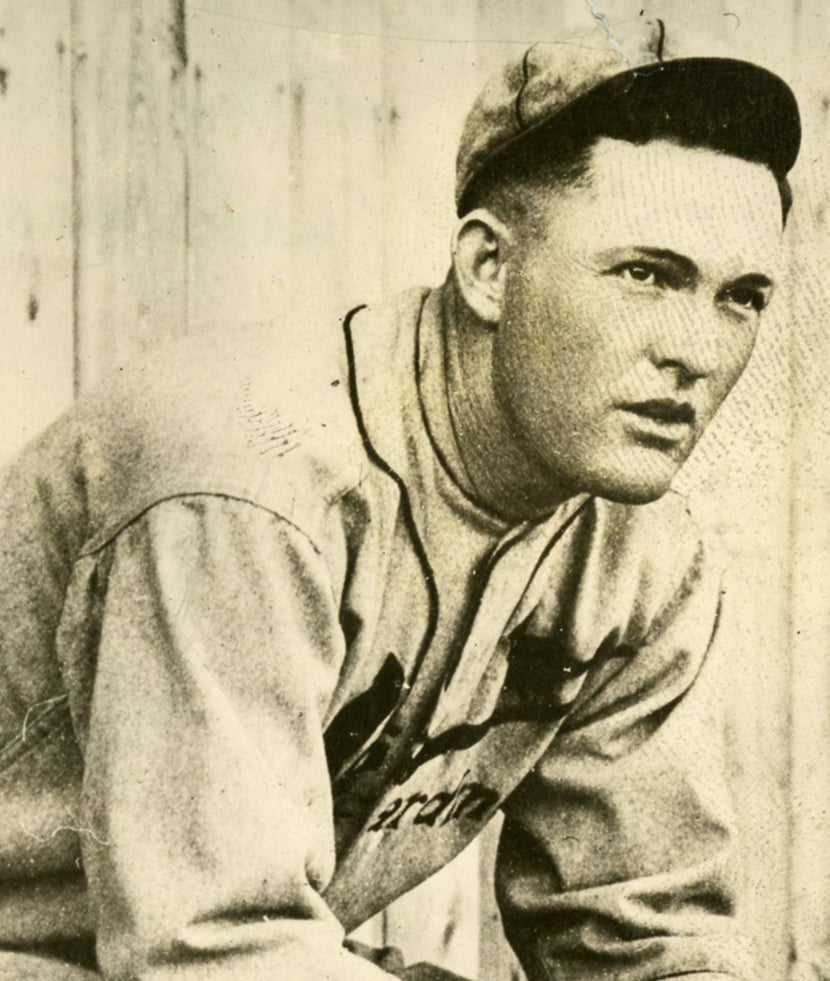

Rogers Hornsby, shown with Cardinals owner Sam Breadon (far left), won batting titles in six consecutive seasons from 1920-25, a big league record. For decades, the record was thought to be held by Ty Cobb with nine straight titles, but research in the 1970s changed the record books. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The league record-keeper in 1910 incorrectly dated the second game of a Tigers vs. Red Sox doubleheader played on Sept. 24 as Sept. 25. Later, when no numbers were found for the second game of Sept.24, the “missing” numbers were re-entered – double-counting that game’s statistics. When the season ended and the mistakes were discovered, the extra numbers were crossed out on each Tigers’ official day-by-day statistics…except Cobb’s.

With this new information, it meant that Hornsby, not Cobb, holds the mark for most consecutive years leading his league in batting average, with six, from 1920 to 1925.

Similarly, in 1929 it was reported in newspapers across the country that the 42-year-old Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, the great right-handed pitcher, had finally become the National League’s career leader in victories. The Hall of Famer, Class of 1938, got credit for the win for the Cardinals in the second game of a doubleheader against the Phillies on Aug. 10, the 373rd of his career, which topped by one the former record held by Christy “Big Six” Mathewson.

Unfortunately for “Old Pete,” now in the twilight of his career, he would not win another game that year because, less than 10 days after his record-breaking triumph, he was sent home by Cards management for the remainder of the 1929 season for breaking training. According to manager Bill McKechnie, he was through with soft treatment of offending players as he had found leniency was not getting results.

“I felt very bad about the matter,” said Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, “but disciplinary methods are entirely up to the manager of the team.”

After contributing to St. Louis winning National League pennants in 1926 and 1928, Alexander was traded to the Phillies in December 1929. But Father Time finally beckoned for the veteran hurler and he was released by Philadelphia in June 1930 after compiling a 0-3 won-loss record for his new squad. This proved to be the end of the line for Alexander, as his big league career was now over after 20 seasons with a 373-208 mark.

“Burt Shotton, the Phillies’ manager, found it a hard job to tell me I was through, and there are no hard feelings,” Alexander said to reporters. “I tried to win, but I couldn’t.”

Whether because of age or his off-the-field proclivities, Alexander didn’t win another major league game after taking over the National League lead from Mathewson. But research in the 1940s discovered a theretofore unknown 1902 triumph for “Matty,” which the major baseball publications of the day soon added to their scrolls, which again tied the two Hall of Famers with a record 373 career Senior Circuit victories.

Grover Cleveland Alexander was thought to have the National League career wins record when he retired with 373 victories. But a decade later, Christy Mathewson was credited with one more win to bring his total to 373, creating a tie atop the record books that still exists today. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

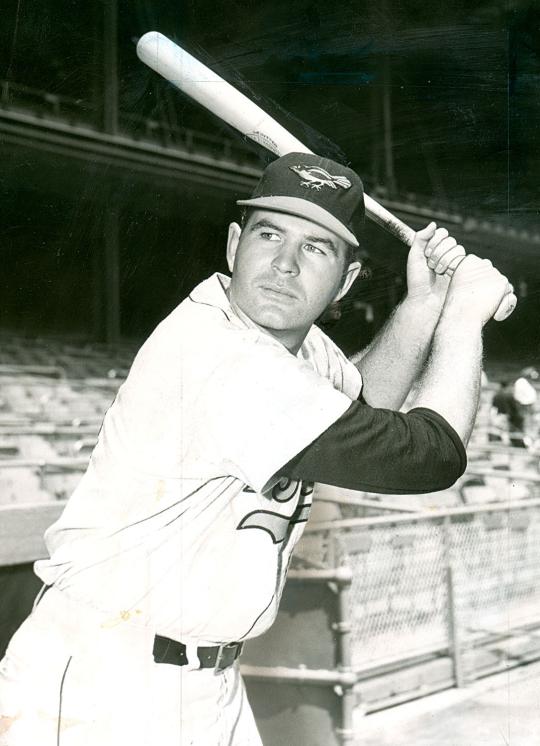

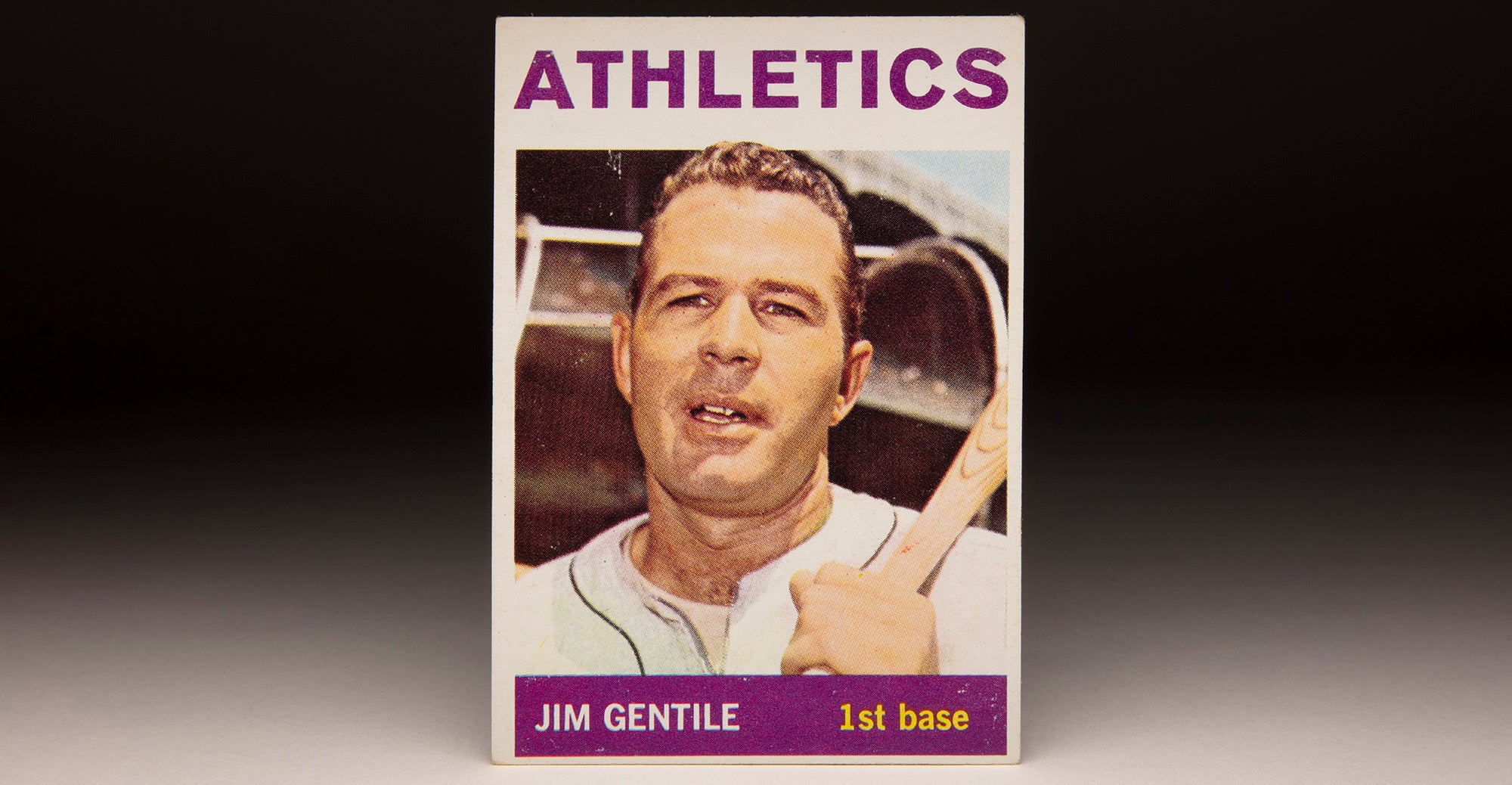

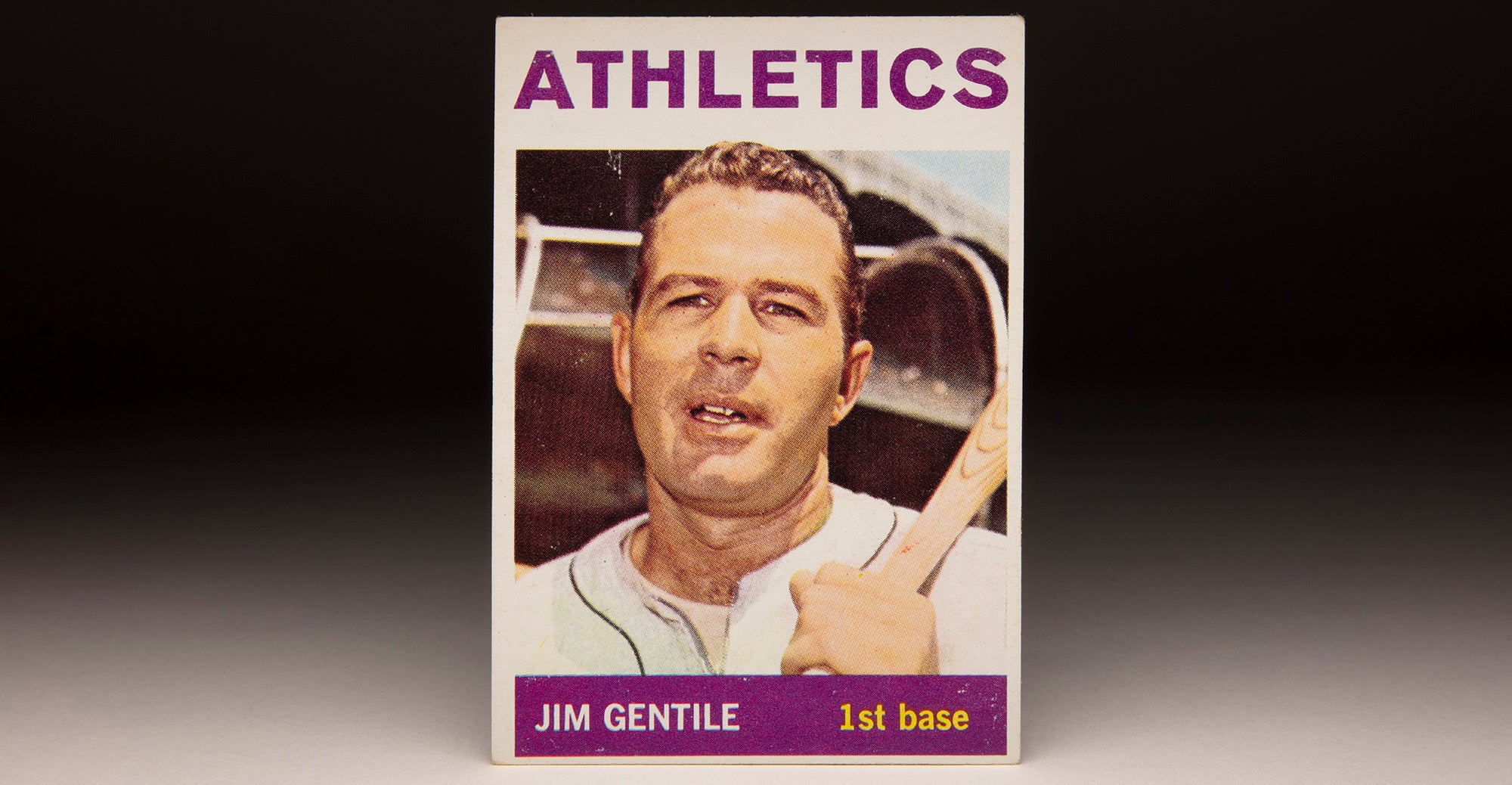

As recently as 2010, another tie was acknowledged publicly with the news that Yankees slugger Roger Maris, through the dogged efforts of baseball researcher Ron Rakowski, had one less run batted in than his league-leading 142 during his famous 1961 season in which he clubbed a then-record 61 home runs. Maris’ reduced RBI total of 141, the result of a run that actually scored on an error, tied him with Baltimore’s Jim Gentile for the American League lead that year.

“I wish I had known that then,” said Gentile, after hearing the news. “The next winter, (general manager) Lee MacPhail said if I had led the league in RBIs, that alone would have been worth an extra $5,000.”

Gentile had the best season of his nine-year big league career in 1961, batting .302 with 46 home runs, 141 RBI, and finishing third in the AL MVP voting behind Maris and Mickey Mantle.

The Orioles would honor Gentile for his belated RBI title before a home game at Camden Yards on Aug. 6, 2010, the ceremony featuring Baltimore President Andy MacPhail, son of Lee MacPhail, presenting the former Orioles first baseman with a $5,000 check.

Unlike a miscalculation ultimately being the cause of a statistical error, sometimes elements outside a player’s control conspire against the reaching of certain lofty heights. Such was the case with Hall of Famers Jimmie Foxx and Stan Musial.

Jim Gentle recorded 141 RBI in 1961, at the time thought to be one fewer than American League-leader Roger Maris. But 21st century research determined that Maris was credited with one more RBI than he had, moving Gentile into a tie atop the season leaderboard. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1932, 24-year-old Philadelphia Athletics first baseman Foxx, coming off three seasons with at least 30 home runs, made an epic run at what was thought of then as an almost unbreakable record: Babe Ruth’s 60 homers hit only five years earlier in 1927.

While an injured wrist and inclement weather may have hampered Foxx’s homer efforts toward the end of the ’32 campaign, the right-handed hitter still finished the year with a .364 batting average while leading the AL with 58 round-trippers, 151 runs scored and 169 RBI on the way to the first of his three MVP Awards. And unlike Ruth in ’27, some ballparks around the AL now had screens over their outfield walls that lessoned the amount of homers allowed there.

“Foxx is the greatest batsman in Major League Baseball today,” declared Ruth after the 1932 season. “There’s no question about that. He’s a swell fellow – well-liked by the players and fans. In fact, he’s such a nice kid I was kind of sorry for him when he came so close to the record and missed.”

In 1951, soon after “Double X” was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, he addressed his 1932 attempt at Ruth’s single-season home run record.

“I hit three drives in 1932 that struck the wires and bounced back. When the Babe hit his 60, those drives would have gone over. But they called the ball in play when I hit ‘em and I was cheated out of three home runs. That would have made 61,” Foxx said. “And know something else. That same year I hit two other home runs in games that were called on account of rain and I didn’t get any credit for them. But what’s the use in crying now?”

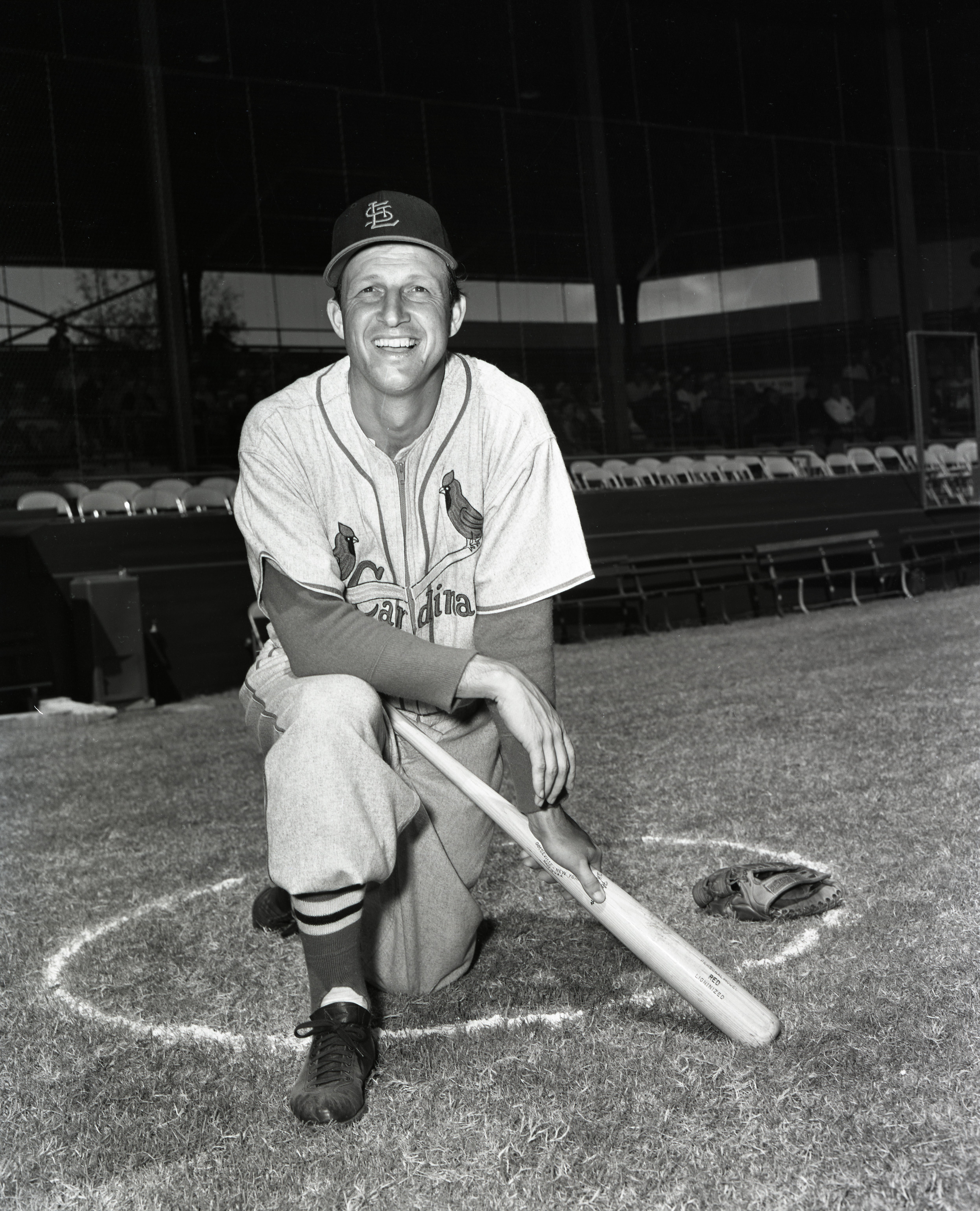

Damp conditions also played a role in Musial not capturing a Triple Crown in 1948. The left-handed-hitting Cardinals star came close, though, leading the NL with a .376 batting average and 131 RBI but his 39 home runs fell one short of the totals put up by the New York Giants’ Johnny Mize and Ralph Kiner of the Pirates. A home run Musial hit in a rained out game that year was nullified.

“I can’t remember who we played,” Musial would say years later, “but if that homer had counted I would’ve been the first Triple Crown winner in the league since Joe Medwick (in 1937).”

But the offensive output was good enough for “Stan the Man” to be presented with his third NL MVP Award in six years. Musial, despite hitting 475 career homers, never led the league. The 39 he slugged in 1948 were a career high.

Sometimes a player’s record is changed as the result of a clarification. In 1991, Major League Baseball’s Committee for Statistical Accuracy, chaired by MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent, defined for the first time what a no-hitter was: “An official no-hit game occurs when a pitcher (or pitchers) allows no hits during the entire course of a game, which consists of at least nine innings.”

“The most exalted category should be reserved for those who pitch nine innings and win,” explained Vincent.

The definition therefore eliminated rain-shortened no-hitters, no-hitters that were broken up in extra innings and eight-inning affairs by a losing team on the road.

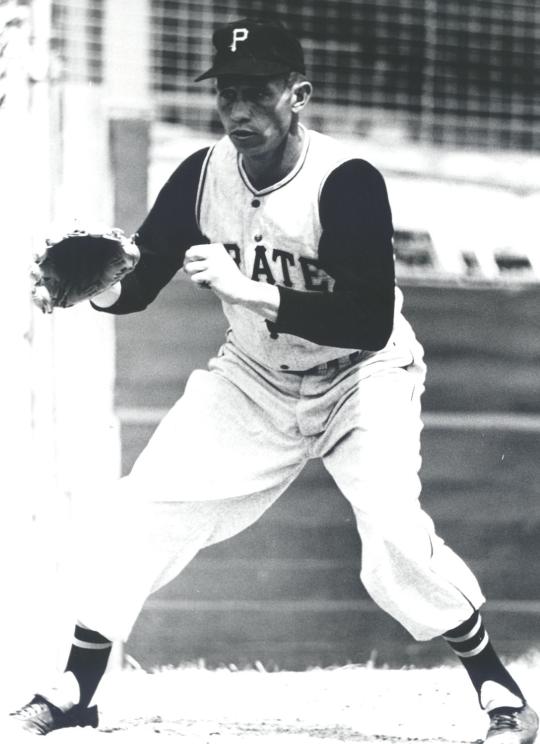

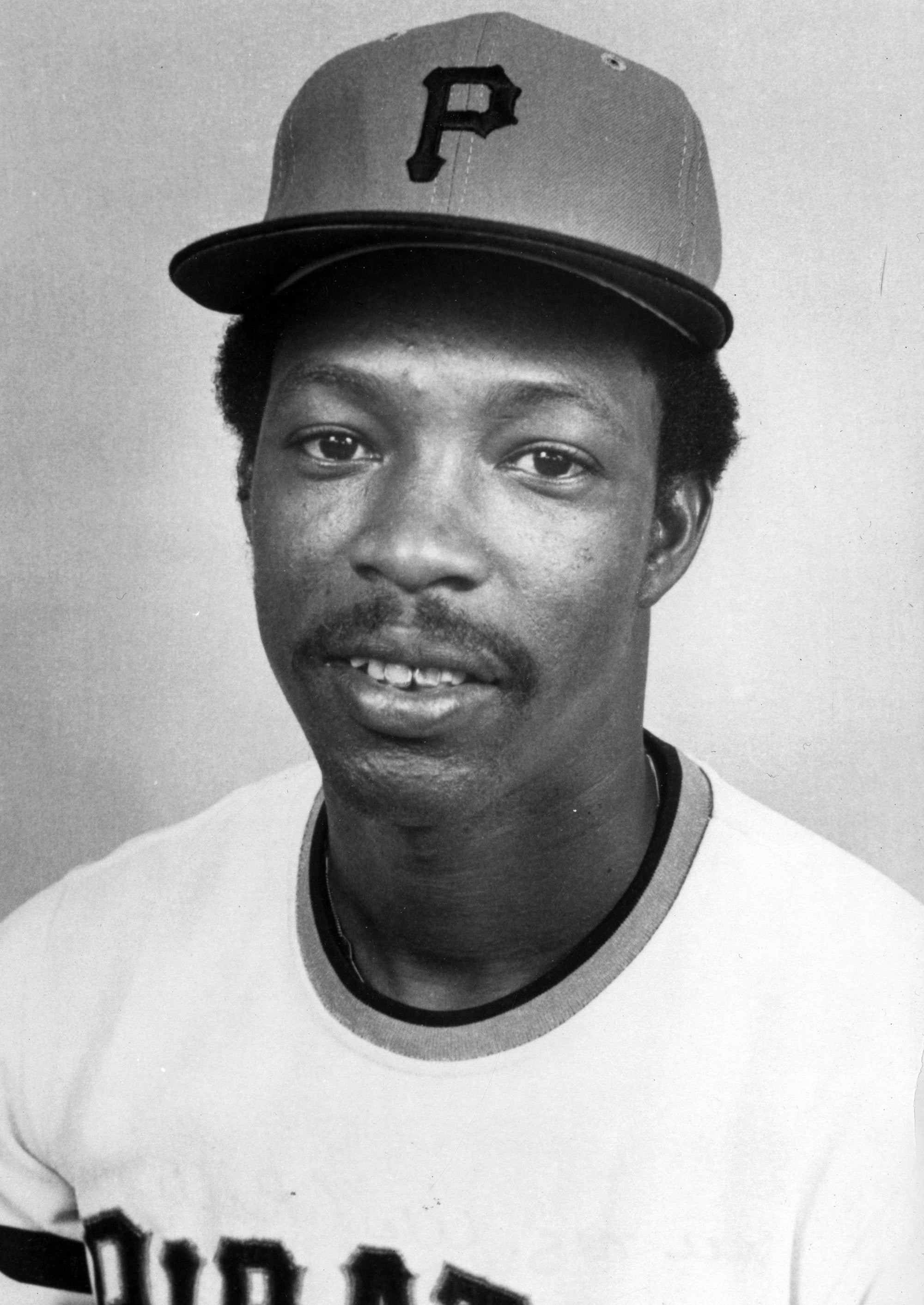

Thus the eight-member committee deleted 50 no-hitters from the scrolls, including one belonging to Harvey Haddix, who tossed 12 perfect innings for the Pirates against the Milwaukee Braves on May 26, 1959, but lost the game in the 13th inning when Joe Adcock hit an RBI double.

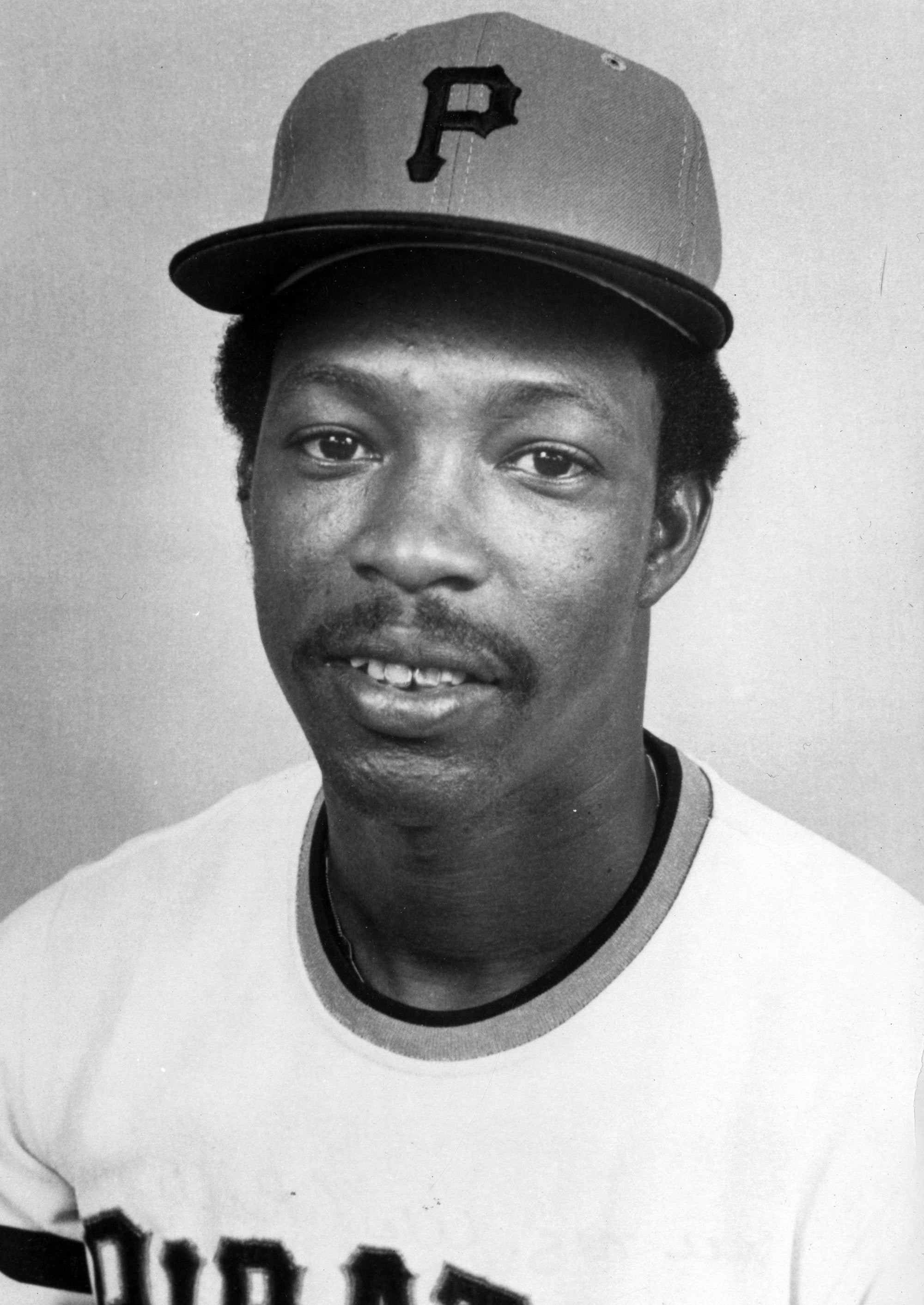

Harvey Haddix of the Pirates pitched 12 perfect innings against the Braves on May 26, 1959, but lost the no-hitter and the game in the 13th inning. MLB considered this a no-hitter for many years, but a change in the statistical record wiped that no-hitter and 49 others off the books in 1991. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

According to Haddix, the change “doesn’t bother me that much. It was really not a no-hitter.”

Pascual Perez of the Montreal Expos was also a victim of the new ruling, having tossed a rain-shortened, five-inning no-hitter against the Phillies on Sept. 24, 1988.

“What can I do? It’s their decision,” Perez said. “Now it’s too late to take it away from me. I have the tape and I have the ball and I’ll keep the no-hitter in my heart.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1964 Topps Jim Gentile

Philadelphia A’s trade Jimmie Foxx to the Boston Red Sox

Musial sets standard with five home runs in doubleheader

Stennett enters record books

#CardCorner: 1964 Topps Jim Gentile

Philadelphia A’s trade Jimmie Foxx to the Boston Red Sox

Musial sets standard with five home runs in doubleheader