"When you are at the ceremony, that’s very emotional, and I think it’s worth it, all the things you went through."

- Home

- Our Stories

- From Monterrey’s Salón de la Fama to Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame

From Monterrey’s Salón de la Fama to Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame

It is not often that a member of another country’s baseball hall of fame visits the United States’ shrine in Cooperstown. But when it happens, the baseball bonds that transcend national borders are evident.

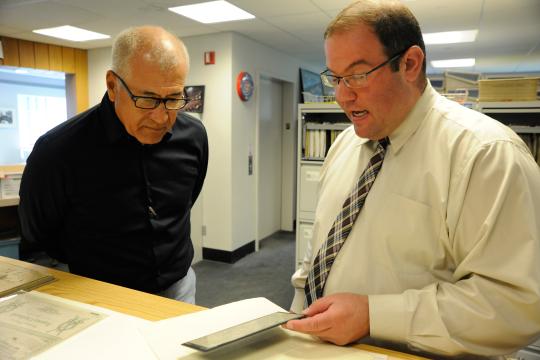

Juan Navarrete, who spent 21 seasons in professional baseball, most of them in the Mexican League, arrived in Cooperstown for the first time two months ago, on July 16. Navarrete, the roving infield and defense instructor in the Oakland Athletics’ minor league system, drove in from the Albany area, where the A’s short-season class-A team, the Vermont Lake Monsters, was in Troy, N.Y., to face the Tri-City ValleyCats.

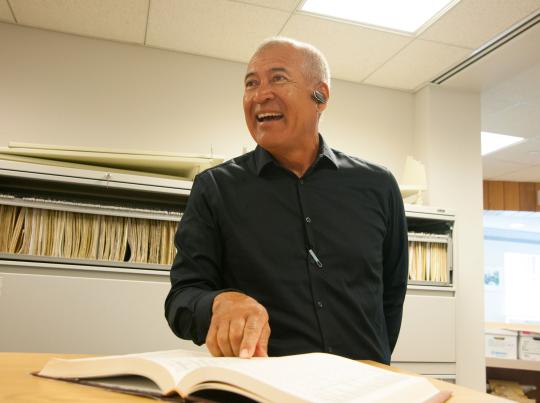

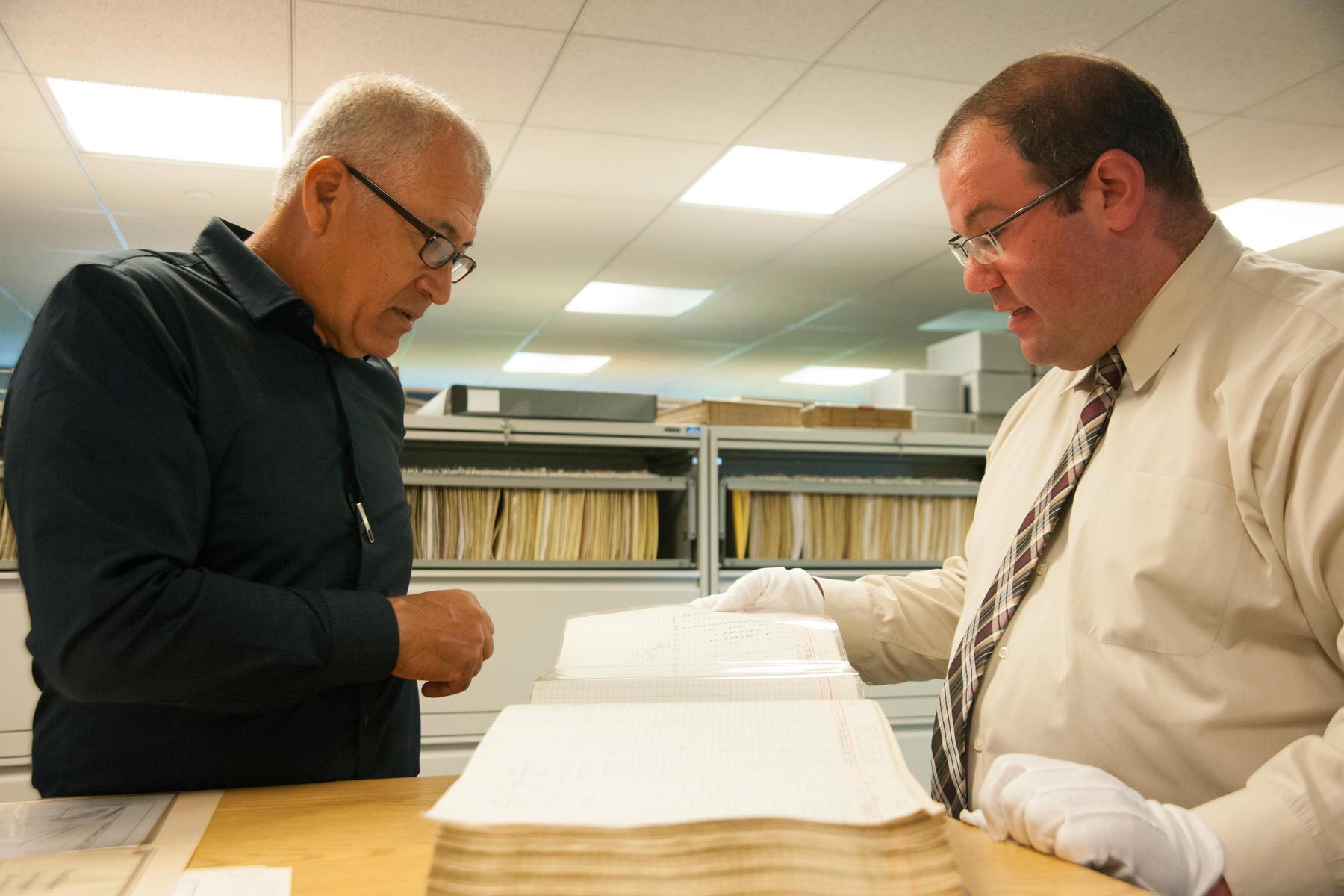

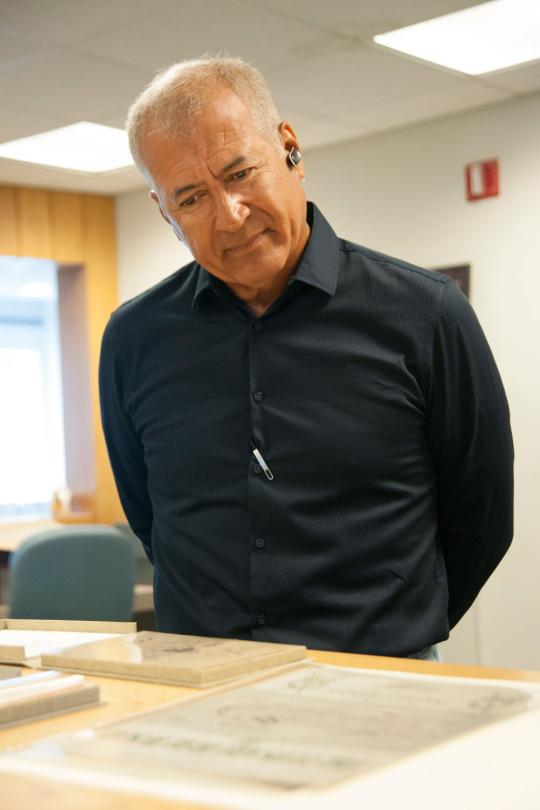

Navarrete, a 1998 inductee of the Salón de la Fama del Beisbol Profesional en México, toured the Hall of Fame and its Library, reminiscing about his own professional baseball career.

Born in Gomez Palacio, Mexico, in 1953, Navarrete came from a baseball-playing family. His father, Hermenegildo, played pro ball in Mexico for the Torreon club, and the younger Navarrete gleaned as much as he could from his dad and family, as well as learning on sandlots and playgrounds in and around his hometown.

“My family, my father, my uncles, my cousins – they all played baseball,” Navarrete remembered. “I grew up watching them, going with them, and seeing them play. I really started loving this game from my childhood, and I think it was a great start.”

Navarrete would soon attract notice from scouts in the Mexican League, and in 1970, at the age of 16, he signed his first professional contract with the Saltillo Saraperos.

“Coming from a baseball family, I really wanted to play professional baseball, no matter what,” he said. “(I didn’t want a) signing bonus or anything like that. It was a thrill for me. It was one of the best things to happen to me at an early age.”

He received 200 pesos a month, to play mostly when Saltillo was either up or behind big. Navarrete laughed when seeing the 1867 illustrated book Baseball as Viewed by a Muffin, realizing that he was “pretty much a muffin” – an early term for a benchwarmer or lesser-skilled player – in his first professional season.

Though Navarrete never thought about it, his father knew Juan had the skills to play in the minor leagues in the United States. After the 1971 Mexican League season, the younger Navarrete was invited to travel to Montreal, where the Expos held a tryout for Latin American players. For him, it was a set of completely new experiences.

“That was my first time on a plane, and I was shocked,” he recalled. “I flew from Mexico City to New York, and I didn’t know what to do. I needed help. Back then, the language barrier and the food, all that stuff – I didn’t care. I was just amazed and grateful to come to the States and give it a try.”

Shortly after, Navarrete received a phone call from the Expos, who were impressed enough with his skills to sign the 18-year-old. Playing the 1972 season with Montreal’s Class A affiliate in West Palm Beach, Navarrete would eventually become teammates that season – and subsequent seasons – with another future Hall of Famer, Gary Carter. Even that early, Navarrete saw Carter’s zest and love for the game.

“He was a very enthusiastic player, and I heard a lot of players, teammates, who would criticize him,” said Navarrete, who would be teammates with Andre Dawson later in his time with the Expos. “Gary, he was a winner. He wanted it and he was hustling. You know, the bad habits, they’re everywhere, from my era up until now. They misunderstood: He was just playing the game. He was running hard from home to first, and some players will look at that the wrong way.

“Nowadays, I still have that in my mind. He earned it. Besides his ability, he put everything on the field, and I learned from that. A lot of good players back then didn’t make it – not because of their abilities but because of their habits.”

As a middle infielder playing mostly at second base, Navarrete quickly rose through the Expos’ farm system and earned his way on to the 40-man roster for two seasons. He recalled those days as he looked at his profiles the Expos’ media guides from 1975 and 1976.

While he played with Montreal’s big league club in spring training, Navarrete would not receive the call to join the Expos during the regular season. After his sixth season with in Expos organization – and fourth season at Triple-A – in 1977, he became a free agent.

The Mariners took a chance on Navarrete, signing him at the end of November 1977, and giving him a non-roster invite to 1978’s big league spring training. However, the opportunity was fleeting, as Seattle sold him back to Saltillo, which came as a huge disappointment to Navarrete.

“I didn’t want to go back to Mexico because I knew I could play. I don’t know what happened, I think something behind [closed] doors,” he said. “All of a sudden, you’re going back to Mexico, and I was so devastated, I didn’t want to play anymore. It was the saddest day of my life.”

Going back to play in the Mexican League came as an unwanted shock to Navarrete, who still received the occasional offer from major-league teams, but he made the best of the situation after a talk with family.

“I went back and I didn’t have any other options, and I didn’t know anything else but to play baseball for a living,” Navarrete explained. “But I had to (continue playing) because I just got married. I started playing through the motions, like a zombie, and thank God one of my uncles came and talked to me. I started realizing this is my life: baseball. I started playing my best, and I think I ended up with a nice career.”

He ended up hitting .327 with 1,979 hits in 1,607 games in the Mexican League, while owning a .252 average in 707 games during his time in the Expos organization.

After playing six seasons for Saltillo, Navarrete took on the dual role of player-manager for the club in 1983, reprising that role from 1984 through 1986. He also was a player-manager for Monterrey Industriales in 1989 before playing one last season in 1990. In addition to all the springs and summers playing baseball, Navarrete spent each winter of his career playing in the Mexican Pacific League and recently received the Benjamín Reyes Trophy as the league’s best manager in the 2014-2015 season.

Navarrete returned to the managerial role on a full-time basis for Saltillo in 1991 and 1992, as well as Tabasco in 1993 and 1994. Despite a sixth-place regular-season finish in the 1993 regular season, Navarrete guided the Olmecas to a league championship.

“In my later years, I wanted to be an instructor, not a manager, in Mexico,” he mentioned. “But there is no other choice to stay in the game in Mexico but as a manager. Even in my last playing years and in my beginning years as a manager, I always thought about (returning to) the states.”

It was a chance encounter at the Winter Meetings in the early 1990s that led him back to baseball in the United States. Navarrete, invited to the meetings by his Mexican club owner, ran into Karl Kuehl, his manager at Double-A Quebec in 1973. Kuehl, by this time an executive in the Oakland organization, invited Navarrete to join the club’s instructional league for a couple of weeks. Those weeks led to a managerial job with Oakland’s rookie-level Arizona League affiliate, and Navarrete has since spent most of the past twenty years with the Athletics organization.

Working with Oakland’s minor leaguers for so long has given Navarrete the chance to see many of his students make the majors. Longtime shortstop Miguel Tejada was one of the first, while current A’s farmhand Max Muncy, who made his major-league debut on April 25, 2015, is a recent notable.

But it is as a teacher and an instructor these days, “passing along the experiences to the young players at all levels,” where Navarrete receives the most fulfillment

“As a manager/instructor with the A’s, I’ve been picking up little things that I think I’ve been trying to help players at all level, including the one who make it to the big leagues,” he said. “Teaching is the thing I enjoy the most.”

In 1998, Navarrete received the call that he would join the other inmortales in Mexico’s Salón de la Fama. The Mexican Professional Baseball Hall of Fame is housed in Monterrey, a hotbed of baseball and where Major League Baseball’s first regular-season games played in Mexico took place, and emotions ran high for Navarrete, who still resides in Mexico.

“When I decided to stop playing – I think all of us say the same thing – I could have played another year or two. Even though I didn’t play in the big leagues, I feel very peaceful with myself and the way I played the game,” he remembered. “I never thought about it when I got the call. When you are at the ceremony, that’s very emotional, and I think it’s worth it, all the things you went through. I keep telling the young players, no matter what, you never know (if you will be a Hall of Famer).”

Being a Hall of Famer and having years of playing and managing experience allows him to impart his wisdom on young ballplayers. He stressed, though, that Hall of Famers can always learn from each other.

“I always like to listen to whoever is inducted,” Navarrete said of Cooperstown’s enshrined greats. “You learn so many things from them. The game is going to be here forever, and we’re still learning. We learn from people who are successful, and those are the things that, now, I can pass along to the new generations.”

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Experience History at the Museum During Hall of Fame Weekend 2016, July 22-25

1991 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bob Stanley

Classic Comeback

Bud Selig’s work as commissioner leads him to Cooperstown’s doorstep

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

Treasures from Cooperstown Coming to Capital Region for Tri-City ValleyCats Game on Wednesday

March Matinee: Meet Hoops Heroes Who Call Cooperstown Home

2016 Hall of Fame Classic Features Baseball’s Biggest Stars in Memorial Day Weekend Legends Game

01.01.2023