- Home

- Our Stories

- Cool Papa Bell earns Hall call

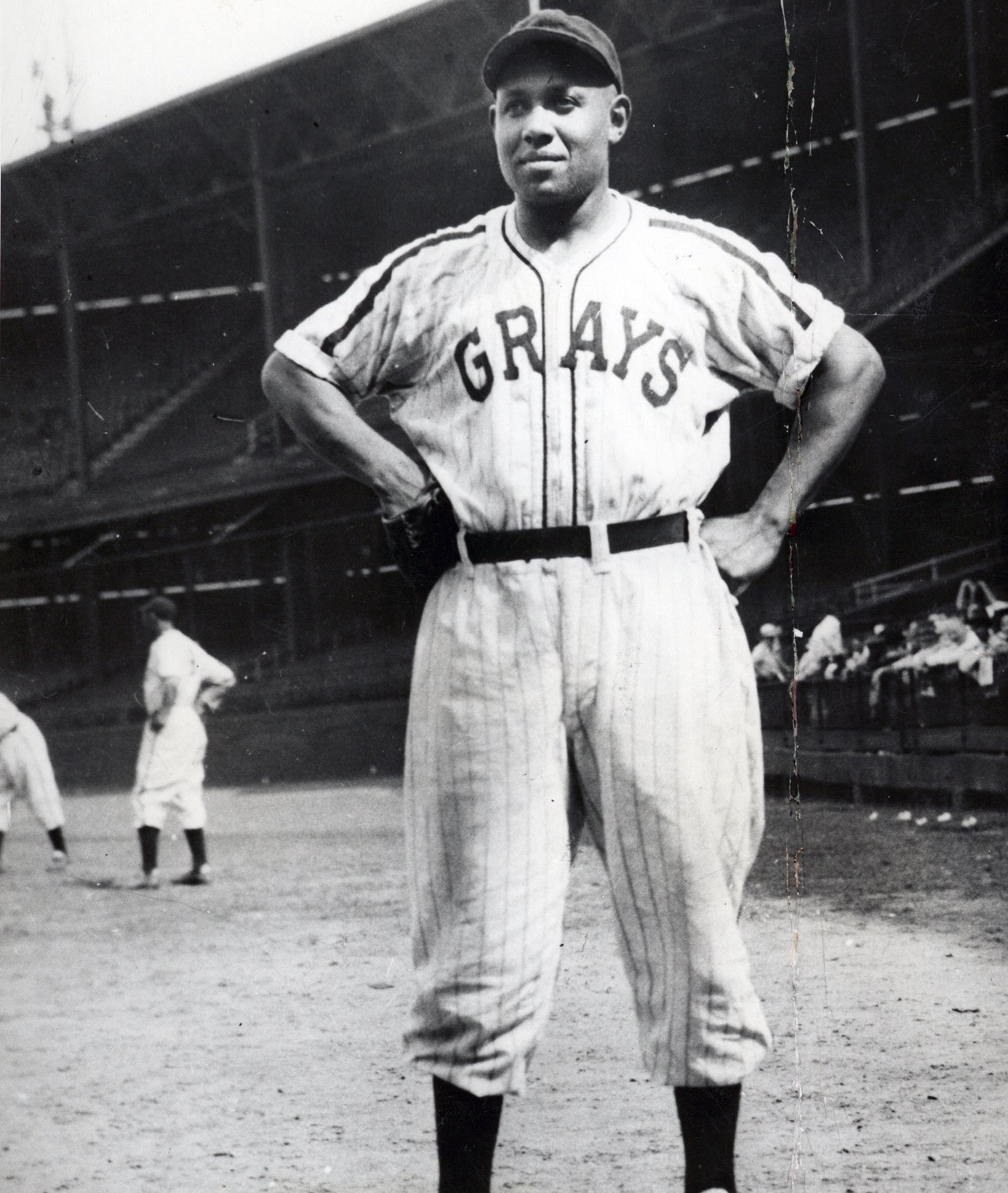

Cool Papa Bell earns Hall call

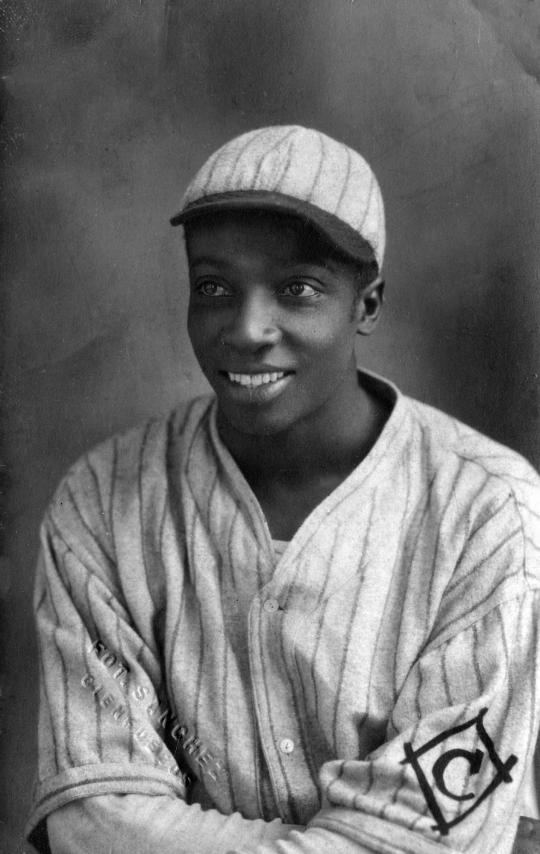

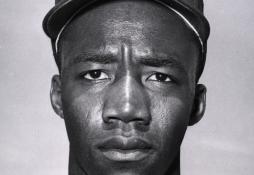

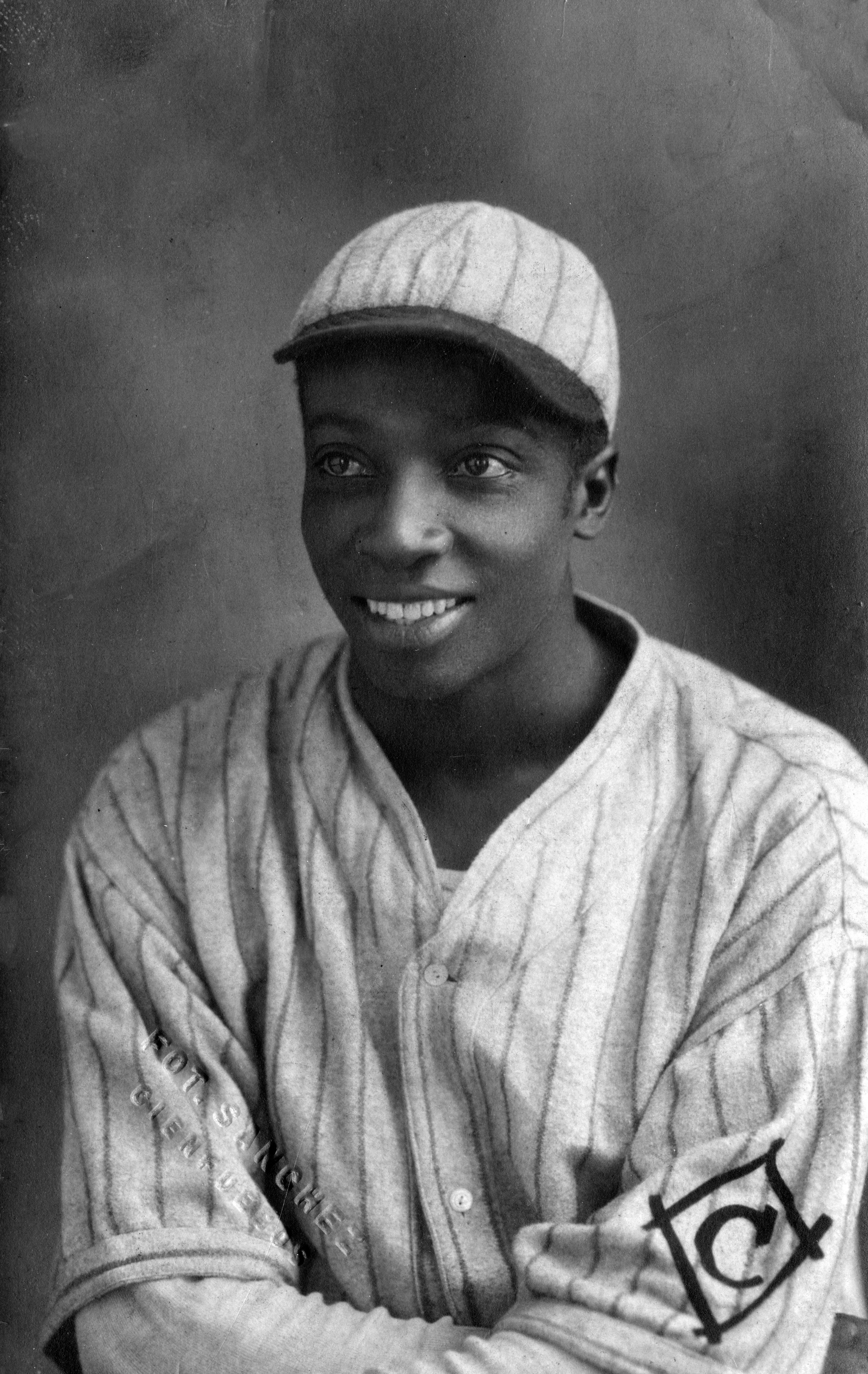

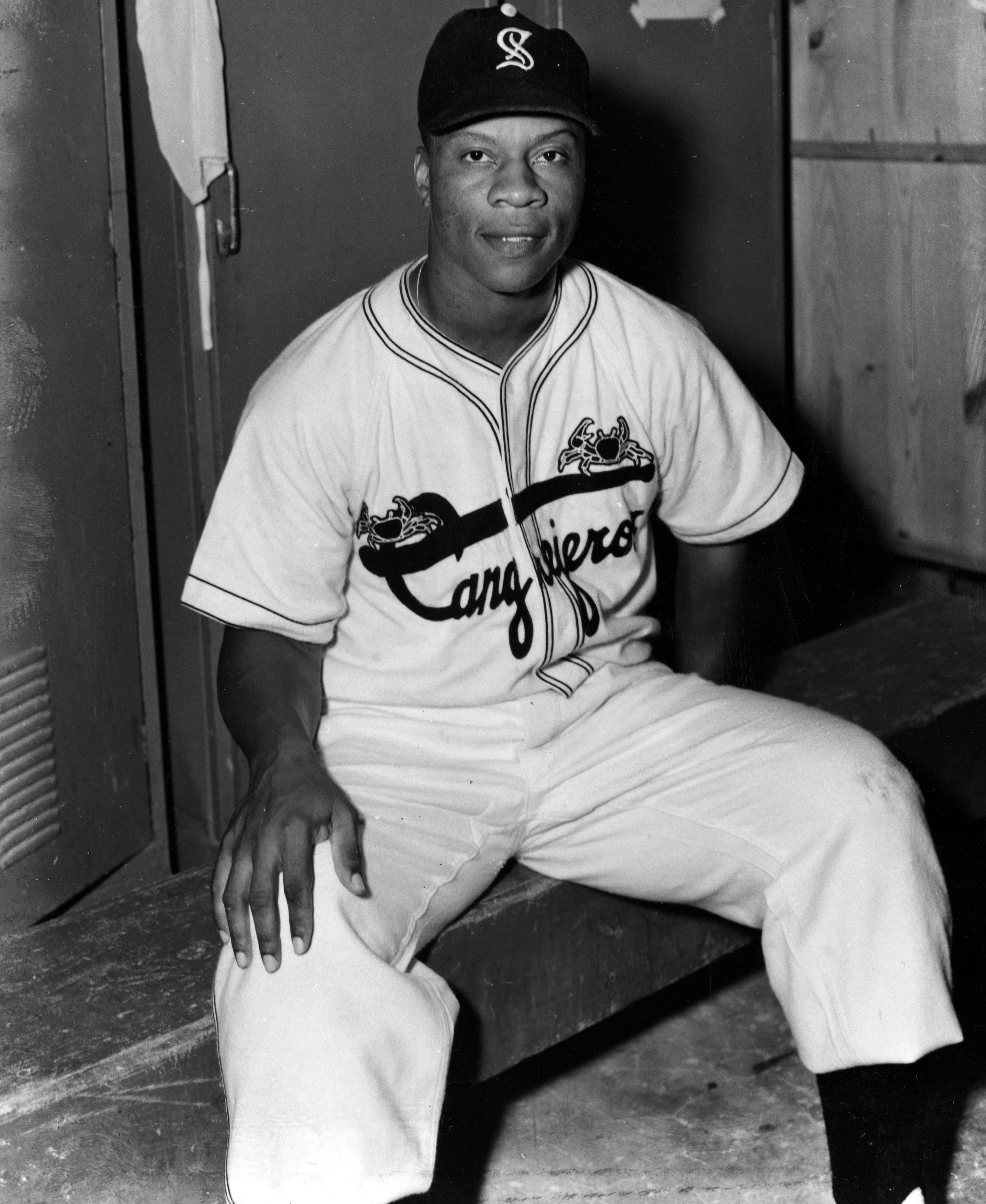

Wherever James “Cool Papa” Bell was going on the diamond, he got there in a hurry.

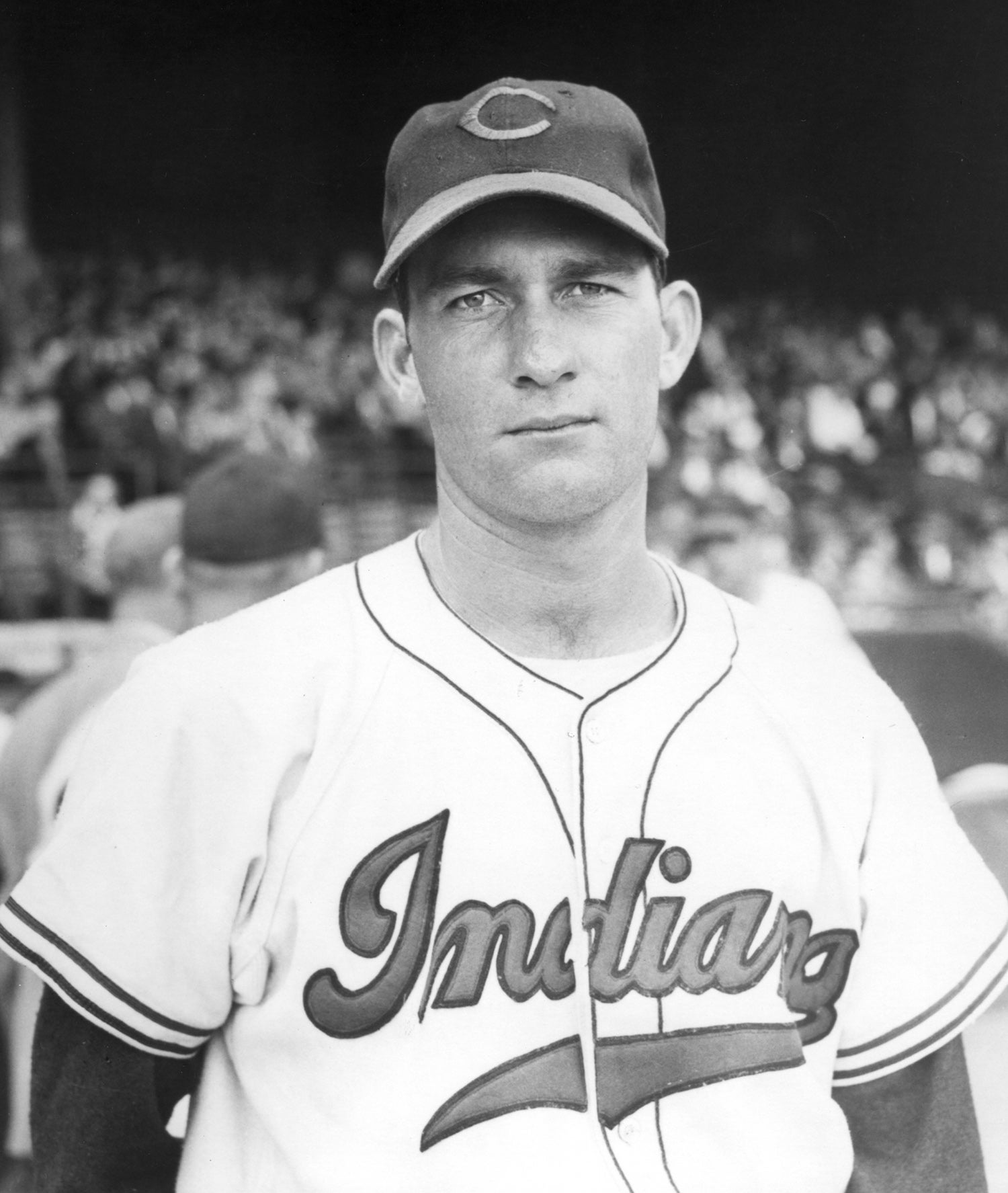

Consider the time he scored from first base on a bunt during a 1948 exhibition versus white major leaguers. Future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon was on the mound. Bell reached second base, and with nobody covering third, he kept running and beat catcher Roy Partee to the bag. Partee had abandoned his post at the plate, so Bell took home, too.

According to Negro League records, Bell stole 285 bases across 21 seasons, leading his league in the category seven times. Countless more steals went unrecorded. The pitcher-turned-center fielder hit .325, earned the nickname “Cool Papa” for his composure under pressure and transcended the game with his blazing speed.

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

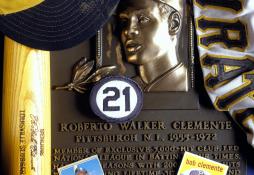

But unlike his baserunning, Bell’s journey to a spot among baseball royalty proved to be anything but quick. On Feb. 13, 1974, 28 years after playing his final professional season with Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays, Bell was elected to the Hall of Fame.

The 70-year-old became the seventh Black player who had played in the Negro Leagues to earn a plaque in Cooperstown. Of that group, only Bell, Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson hadn’t appeared in an American or National League game.

Asked if the news was the greatest thrill of his life, Bell told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “No, it’s my biggest honor. My biggest thrill was when they opened the door in the majors for the Black players.”

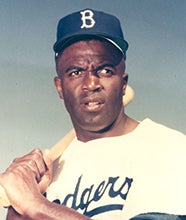

Bell retired after the 1946 season and Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers the following spring. “By the time Jackie Robinson came along and broke the color line,” Bell told the New York Daily News, “I was too old. I was over the hill as a player.”

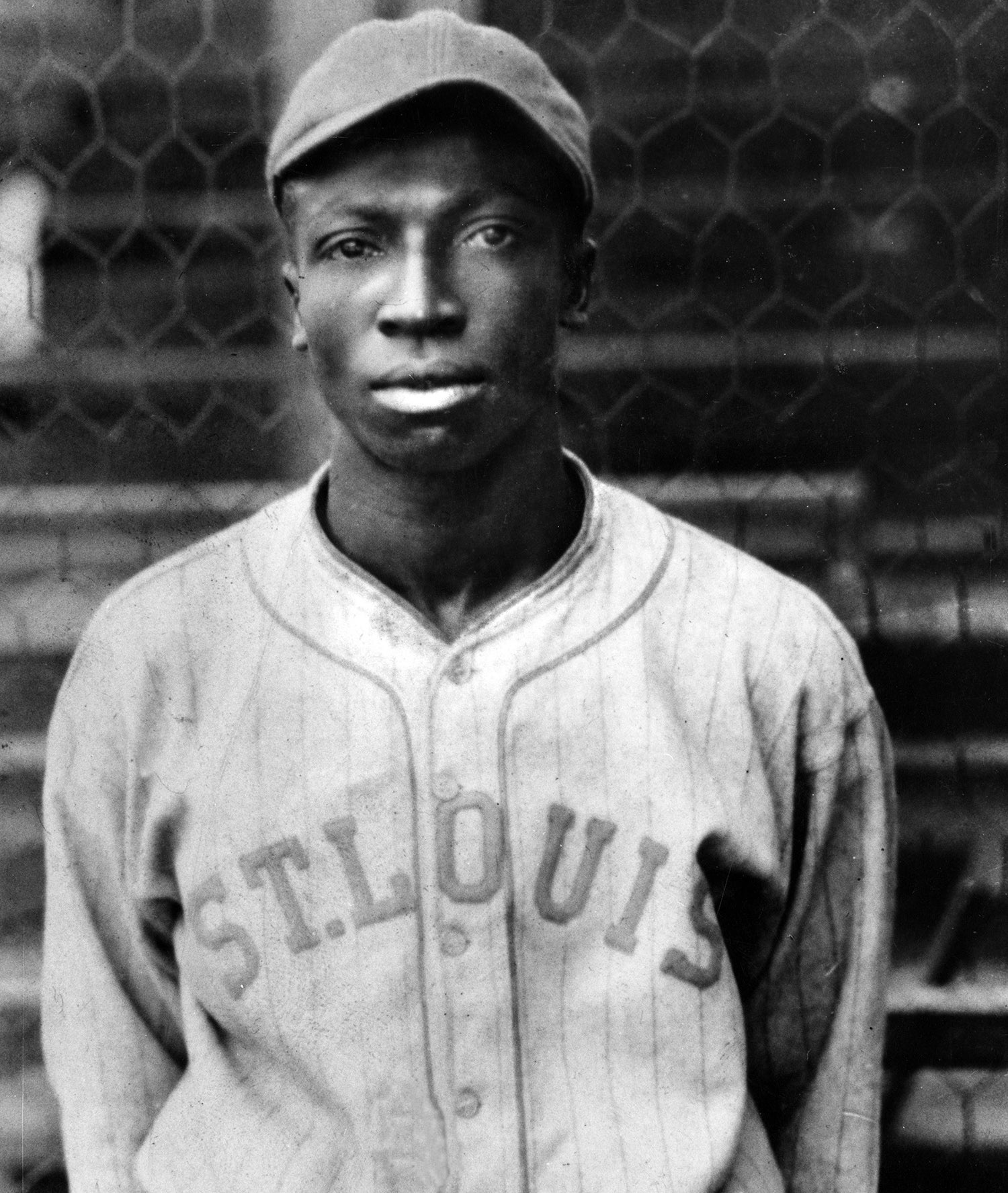

Though deprived of an opportunity in integrated ball, Bell enjoyed one of Black baseball’s longest and most prolific careers. It began in 1922 with the first Negro National League’s St. Louis Stars, who reportedly paid him just $90 a month at first. He perennially hit above .300 in that league before it crumbled under the Great Depression in the early 1930s. His 1932 in the East-West League, including stints with the Detroit Wolves and the Grays, proved similarly successful. Bell then played 10 more seasons — nine with the second Negro National League and another with the Negro American League.

As he journeyed from one storied Black club to the next, Bell and his speed became stuff of legend. But in reflection, Bell attributed his marvelous baserunning to more than just speed.

“That’s just part of it,” he told the Daily News. “It’s really a matter of head-up running and keeping the defense off stride. A lot of runners are satisfied with getting just one base, I wasn’t.”

This aggressiveness helped Bell rise to the top of the Black baseball world, but no further. He could neither play with white stars nor sit with their white fans — Bell recalled sitting in separate bleachers when attending white major league games. Segregation, Bell recognized, extended far beyond himself and baseball.

“Life was that way then,” he told the Post-Gazette. “I lived in that time… But even so, I didn’t feel any difficulty. It was that way when I was born in Starkville, Miss., it was that way when I worked in the packinghouse in St. Louis before I played baseball. People lived that life before I did.”

Bell’s terrific career stacked up with those of his white counterparts, even if a large chunk of the baseball world had neglected to acknowledge that. With the call from Cooperstown, the speedster finally earned a spot alongside them in the Hall of Fame Plaque Gallery.

Justin Alpert is a digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Fast feet, Cool shoes

Playing it Cool

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

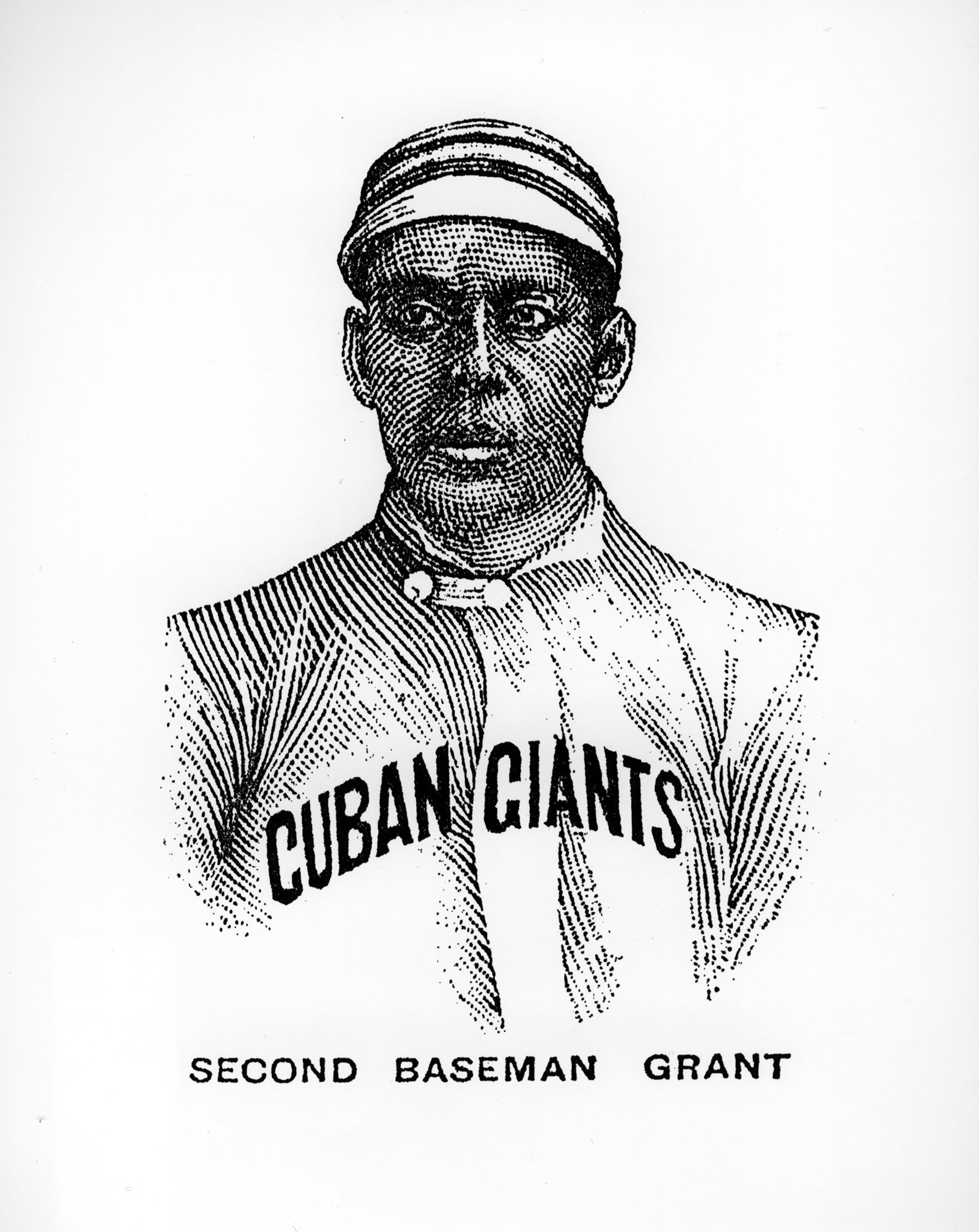

Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

Brown’s lone big league homer made history

Related Stories

Boudreau’s heroics lead Cleveland to title

Irvin and Thompson debut for Giants

#Shortstops: Making a (fashion) statement

Baseball and the Funny Papers

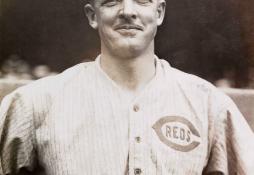

Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

Commissioner Landis frees 74 Cardinals farmhands

The complete story of Jackie

#Shortstops: Art of the pitcher

Hall to Honor Curt Flood’s Legacy, World War II Players during Awards Presentation at HOF Weekend

01.01.2023