- Home

- Our Stories

- Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

One may be the loneliest number, but two might be the least appreciated. History tends to forget those who come in second.

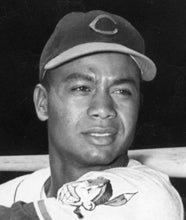

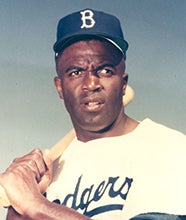

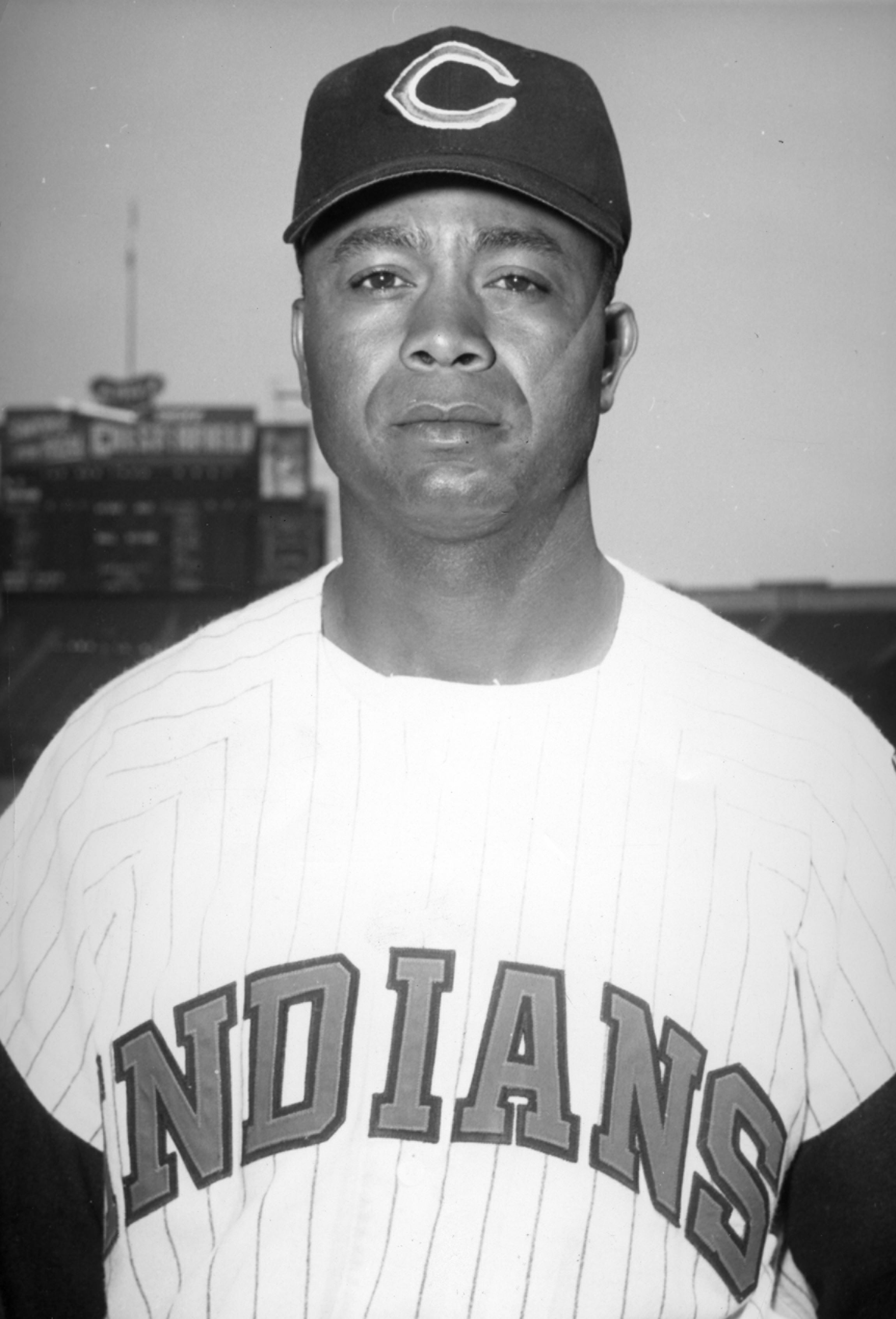

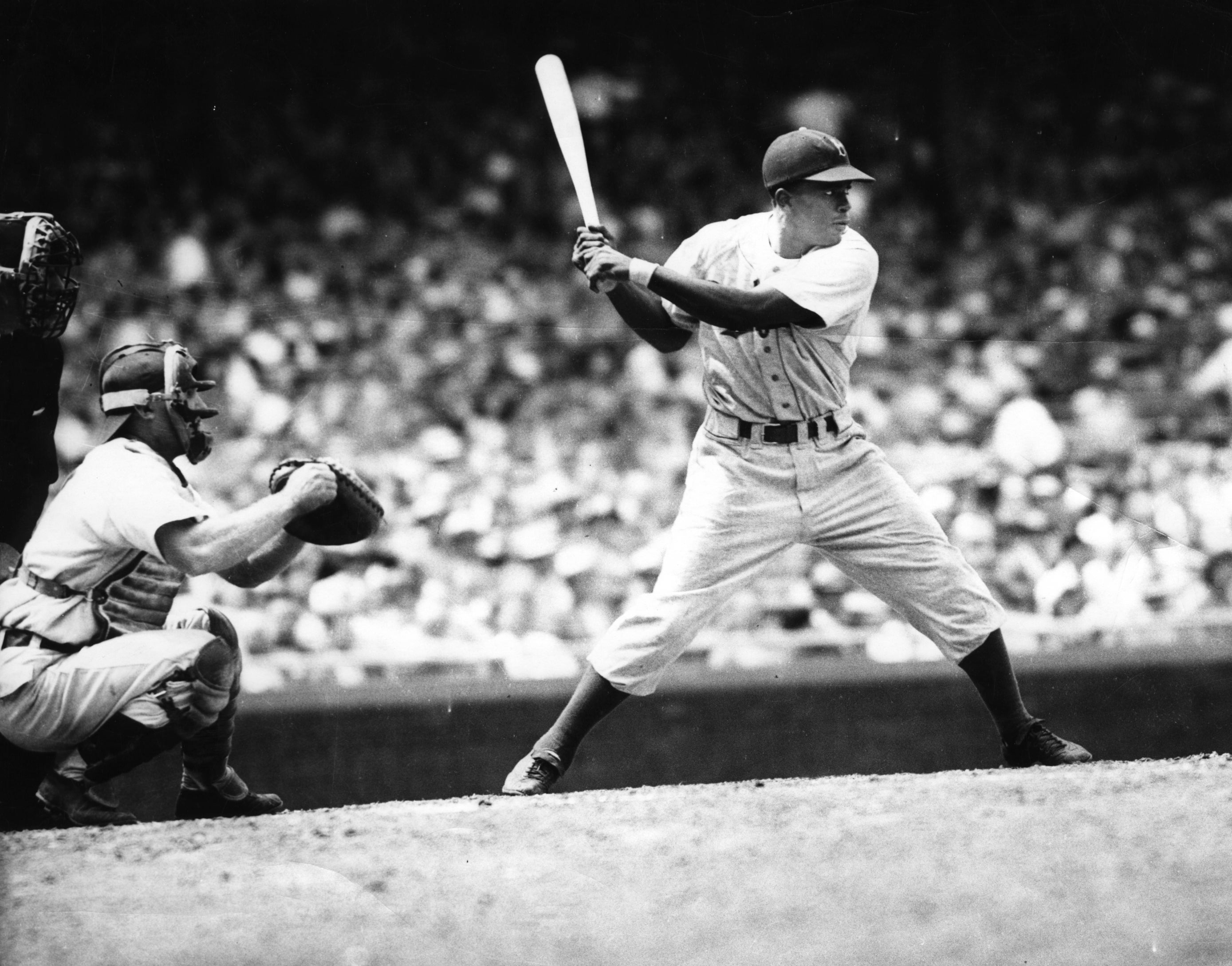

And so it was for Larry Doby, who spent decades in the enormous shadow cast by his friend and fellow trailblazer Jackie Robinson. Eleven weeks after Robinson integrated the National League, Doby took a Louisville Slugger to the American League’s color barrier, jumping directly from the Negro Leagues to the Cleveland Indians. He would be forced to negotiate bigoted basepaths similar to ones Robinson traversed. And he would have to do so in the same restrained manner, turning the other cheek to beanballs, bottles and epithets hurled his way.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Over time, Robinson would be celebrated for the courageous role he played in helping baseball and America become more inclusive. Doby, meanwhile, would wait a bit longer for his recognition.

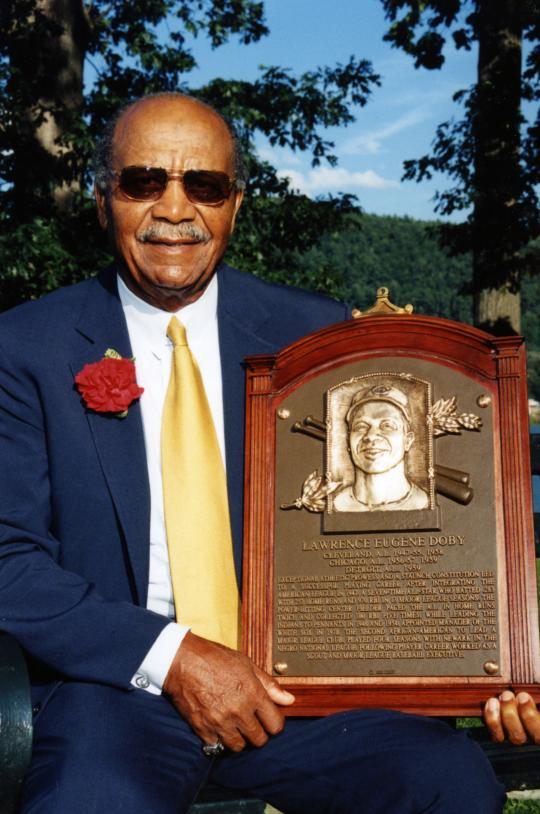

It wasn’t until July 26, 1998, that this pioneer who followed a pioneer received his just due with induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. On that warm summer day a quarter century ago, the seven-time AL All-Star and two-time home run champion was made to feel second to none. That evening, after the festivities concluded, Doby and his wife, Helyn, shared a quiet moment in the room where his bronze plaque now hung among baseball’s immortals.

“This is it,’’ he said, softly. “We’ve arrived.”

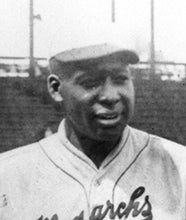

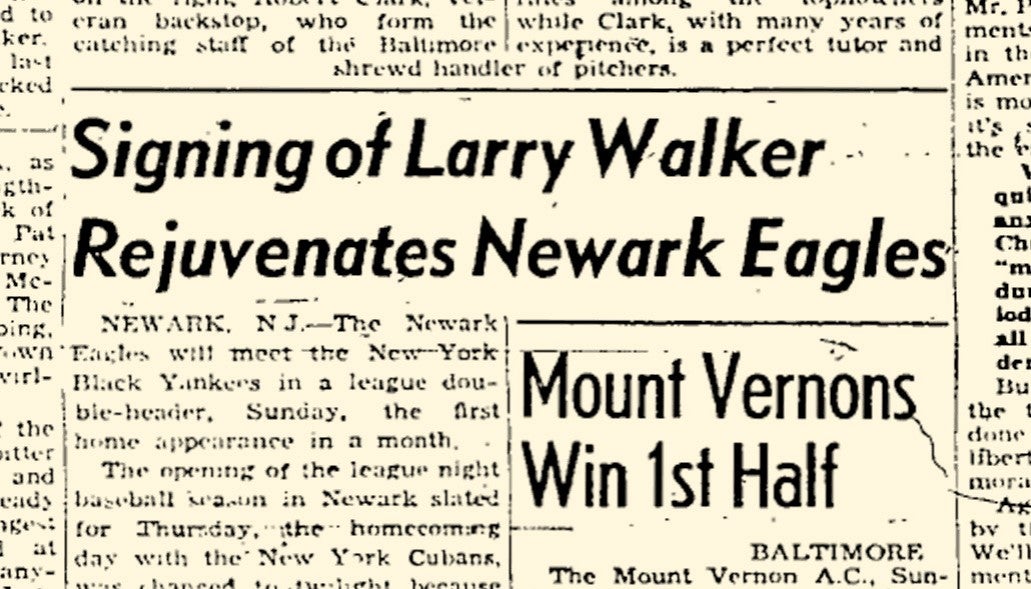

Doby’s journey to Cooperstown took root in Paterson, N.J., where he led Eastside High School to a state football championship and earned a basketball scholarship to Long Island University. His best sport, though, was baseball, and as a 17-year-old he was so good that Effa Manley, the Hall of Fame’s only female member, signed him to play for her Newark Eagles in the Negro National League in 1942 following a tryout at Paterson’s historic Hinchliffe Stadium. To protect his amateur status, Doby played under the alias Larry Walker.

Despite competing against seasoned pros several years his senior, he held his own his rookie season. That fall, Doby began studies at LIU, but after one semester, he transferred to Virginia Union College to play basketball and participate in the school’s ROTC program. Before his freshman year ended, he was drafted and served in the Pacific theater with the Navy during World War II.

While in the military, he played on several base teams, and his skills caught the eye of many, including Washington slugger Mickey Vernon, who was so impressed he wrote Senators owner Clark Griffith, urging him to sign Doby if Major League Baseball ever allowed integration. Doby’s dreams of that happening were buoyed by the news the Brooklyn Dodgers had signed Jackie Robinson to a minor league contract and assigned him to spend the 1946 season with Montreal of the International League.

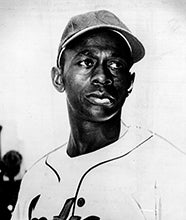

Upon receiving his honorable discharge after the war, Doby returned to the Eagles, powering them to a Negro League World Series title against a stacked Kansas City Monarchs team featuring Satchel Paige.

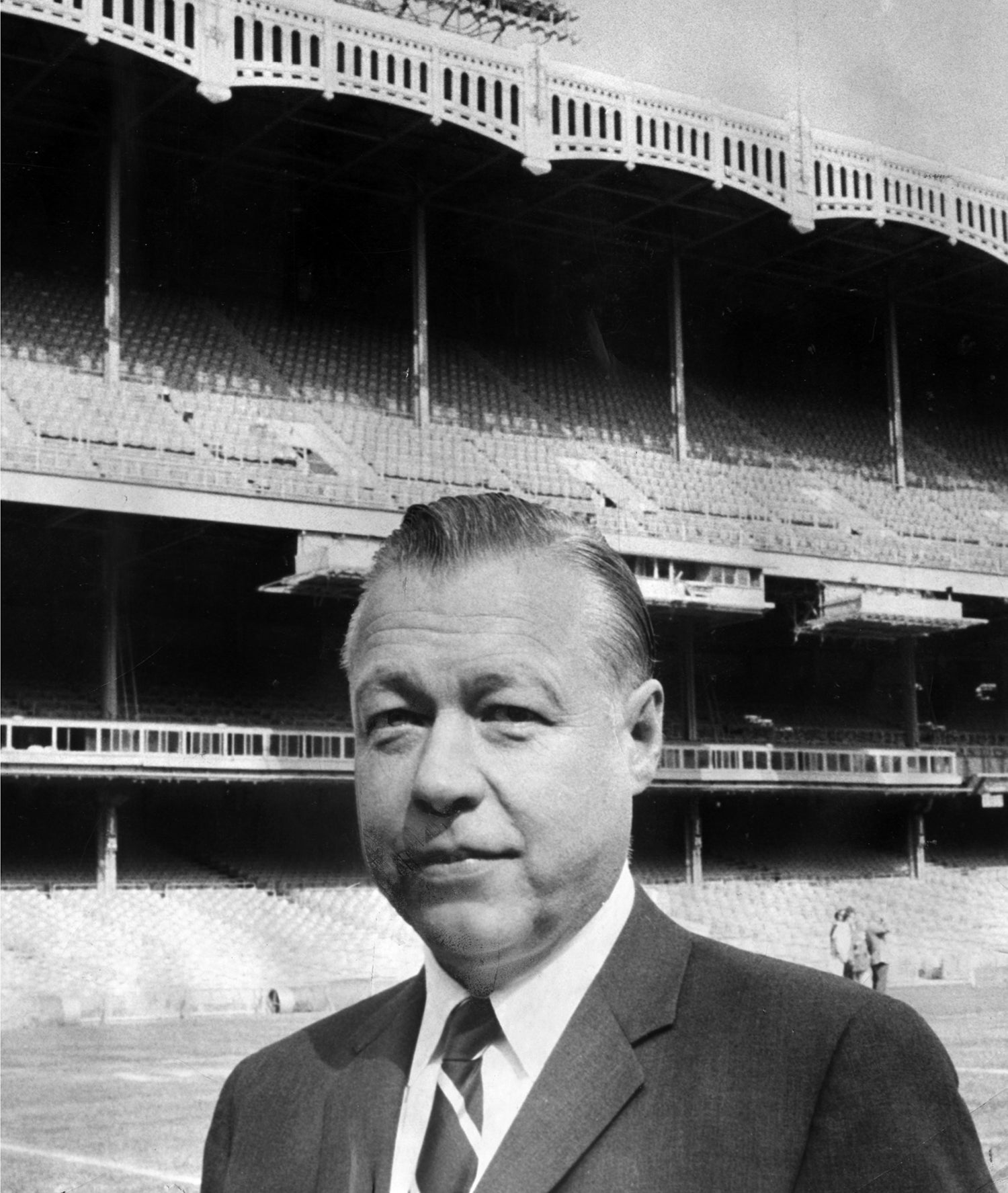

Robinson made his historic NL debut on April 15, 1947. Around the same time — unbeknownst to Doby — Indians owner Bill Veeck was secretly negotiating with Manley to acquire the Newark slugger. Cleveland scout Bill Killefer told Veeck that Doby had the ideal talent and temperament to handle the racial slings and arrows he would face while playing with and against whites. Unlike Rickey, who poached talent from the Negro Leagues without compensation, Veeck paid $10,000 to purchase Doby’s contract and agreed to tack on $5,000 if the then-second baseman stuck on the Indians roster for 30 days.

Taking a different approach than Rickey had with Robinson, Veeck wanted Doby to forego the minors and jump directly from the National Negro League to the AL. Doby’s sterling 1947 stats – including a .415 batting average at the season’s halfway point —indicated he was ready to make the move.

On the Fourth of July, Doby and Louis Jones, an African-American public relations assistant hired by Veeck, boarded a train from Newark to Chicago, where Doby officially joined the Indians for their road game against the White Sox in Comiskey Park the next day. Upon arriving in the Windy City, he was greeted by Veeck. After exchanging hugs and pleasantries, Veeck grew serious, imparting advice echoing what Rickey told Robinson three months earlier. No matter how bad it got, Doby would have to refrain from retaliating against hostile players and fans, because if he did, integration would be set back for years. Like Robinson, Doby understood he wasn’t playing just for himself. America would be watching. The burdens were enormous.

As Cleveland’s newest player signed his contract a few hours before his debut, Veeck offered words of encouragement. “Just remember,’’ he said within earshot of reporters, “they play with a little white ball and a stick of wood up here, just like they did in your league.” Manager Lou Boudreau then took Doby around the locker room and introduced him to each of his new teammates.

“I stuck out my hand,’’ Doby recalled in a 2012 interview with Newark Star-Ledger columnist Jerry Izenberg. “Very few hands came back in return. Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.’”

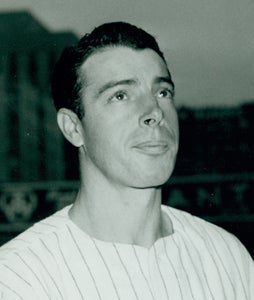

Several teammates turned their backs on him. It only got worse when he took the field. His teammates began playing catch, but no one asked him to join in. For three minutes that felt like an eternity, Doby stood by himself, humiliated and in disbelief. Finally, Joe Gordon ended the freeze-out by tossing him a ball. It was a gesture Doby never forgot. The two would become good friends.

Doby pinch-hit and struck out in his first MLB at-bat that day, and after the game was further reminded of the isolation he would be facing when he was driven not to the team’s hotel, but to a hotel in a Black neighborhood.

Like Robinson, he was subjected to fastballs to the ribs, spikes to the shins and bottles tossed from the stands. An infielder even spat tobacco juice into his face as he slid into second base. He played in just 29 games that season, batting .156. Occasional phone calls with Robinson helped him maintain his sanity. The two men formed an inseparable bond. When Jackie died in 1972, Doby was asked to be one of his pallbearers.

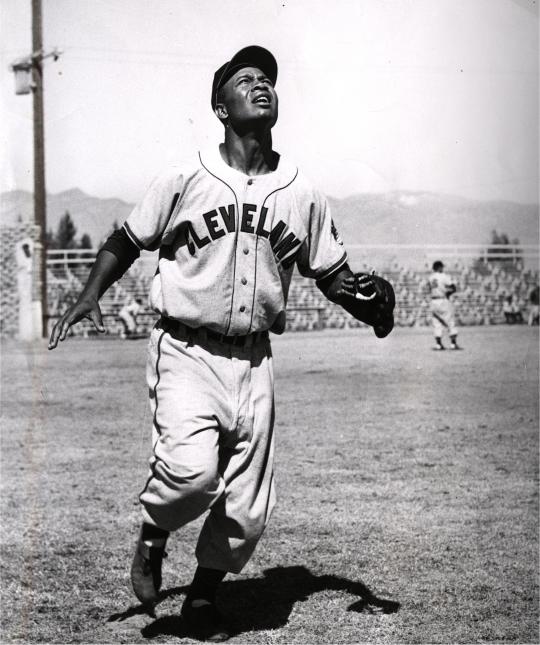

During Spring Training in 1948, Doby switched from second base to center field and was a natural from the get-go. In one of the final exhibition games that March, he cemented a roster spot by smashing a homer that traveled an estimated 550 feet. Doby played a pivotal role in the Indians winning the pennant that season, batting .301 with 14 homers and 66 runs batted in. And his impact would be felt in the World Series when he hit .318 to catapult Cleveland to its first championship since 1920. The high point came in Game 4 when Doby became the first Black player to homer in an AL/NL World Series game. His blast provided the Indians with their second run, which would be all they needed as Steve Gromek outdueled Boston Braves counterpart Johnny Sain for a 2-1 victory.

Of greater significance was the photograph that appeared in newspapers across the country the following day. It was taken in the clubhouse after the game and showed Doby and Gromek joyously hugging each other.

“I don’t know if America had seen many photographs of a Black man and a white man embracing one another before,’’ said author/historian Larry Lester, a curatorial consultant for the Hall of Fame’s ongoing Black Baseball Initiative. “It was a signature moment in the integration of baseball.”

And a signature moment for Doby, too.

“It wasn’t planned,’’ Doby said. “It just happened spontaneously. For me, that photograph was more rewarding than the homer.”

In 1949, Doby clubbed 24 home runs, drove in 85 runs and batted .280, and joined Robinson, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe as the first Black players to appear in an AL/NL All-Star Game. After Doby compiled a .326 average with 25 homers and 102 RBI in 1950, the Sporting News called him the best center fielder in baseball. He wound up being named to seven AL All-Star teams and twice led the league in homers. He finished his AL career with 253 home runs, 970 RBI and a .283 batting average over 10 seasons with Cleveland, three with the White Sox and one with the Detroit Tigers. The statistics were remarkable, considering the circumstances he had to overcome.

“I fought back by hitting the ball as far as I could,’’ Doby said. “That was my answer.”

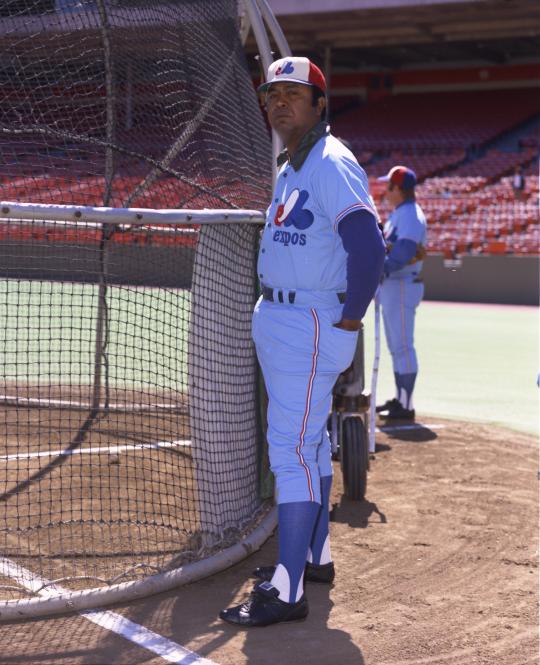

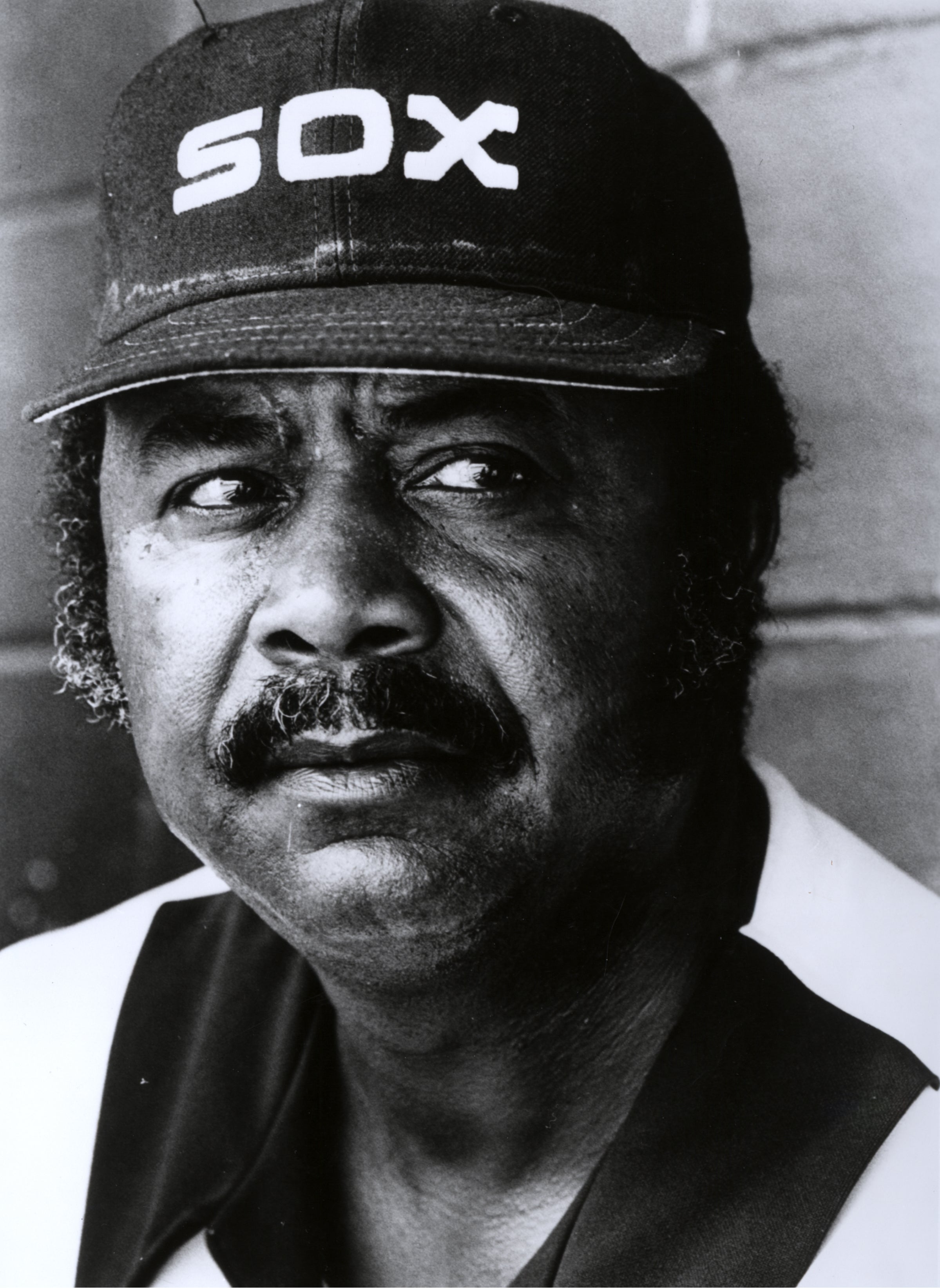

After his playing career, Doby spent time as an MLB scout and coach — serving as Andre Dawson’s first hitting coach, among other roles — and as early as 1971 expressed an interest in managing. On June 30, 1978, he became the second Black man to cross another baseball color line, taking charge of the White Sox three seasons after Frank Robinson became the first Black manager in AL/NL history. Doby returned to his role as the team’s batting coach in 1979, then left to become the director of communications and community affairs for the NBA’s New Jersey Nets. He came back to MLB in 1995 as an assistant to AL President Gene Budig.

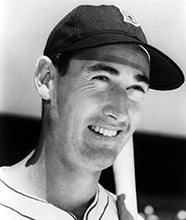

On March 3, 1998, Doby received a long-awaited phone call from Ted Williams informing him the Veterans Committee had voted him into the Hall of Fame.

“I feel like a bale of cotton has been lifted from my shoulders,” Doby told reporters.

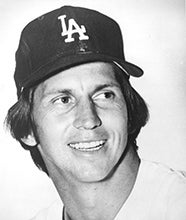

Four months later, this quiet, unassuming man was in Cooperstown, joining the Class of 1998 — Don Sutton, Lee MacPhail, Bullet Joe Rogan and George Davis — as the Hall’s newest members. True to his grateful and graceful nature, Doby chose to accentuate the positives during his induction speech.

“You know, it’s a very tough thing to look back and think about things that were probably negative,’’ he said. “But you put those things on the back burner. You’re proud and happy that you’ve been part of integrating baseball, to show people that we can live together, that we can work together, that we can play together and that we can be successful together.”

Doby died of cancer on June 18, 2003, at the age of 79. The Indians (now the Guardians) feted him by retiring his No. 14 and erecting a statue of him outside Progressive Field. In 2012, the U.S. Postal Service commemorated Doby, Joe DiMaggio, Willie Stargell and Williams with postage stamps.

As one scribe wrote, Doby was proof the seed Jackie planted had taken root. “I’ll take second,’’ Doby told reporters the day he was inducted. “Second ain’t all that bad, baby.”

Scott Pitoniak is an author and nationally honored journalist residing in Penfield, N.Y. His latest book is “Remembrances of Swings Past: A Lifetime of Baseball Stories.”

Related Stories

Doby blazed trails on, off field

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

Larry Walker has been a Hall of Famer for years, thanks to Larry Doby

Doby made history with Indians

When Robinson signed with Montreal, baseball and America changed forever

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

Black Baseball Initiative engages students with crucial history lessons

BASE Race Returns to Cooperstown May 28

Black Baseball Initiative engages students with crucial history lessons

The Winter of Baseball Life

He Never Complained

Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

Wendell Smith Chronology

01.01.2023

2015 HALL OF FAME BALLOT OUT TODAY

01.01.2023